Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a relatively common, though still not fully understood, chronic hormonal condition. PCOS can cause a range of symptoms, including menstrual cycle disruptions and metabolic issues, though how it looks can vary a lot from person to person.

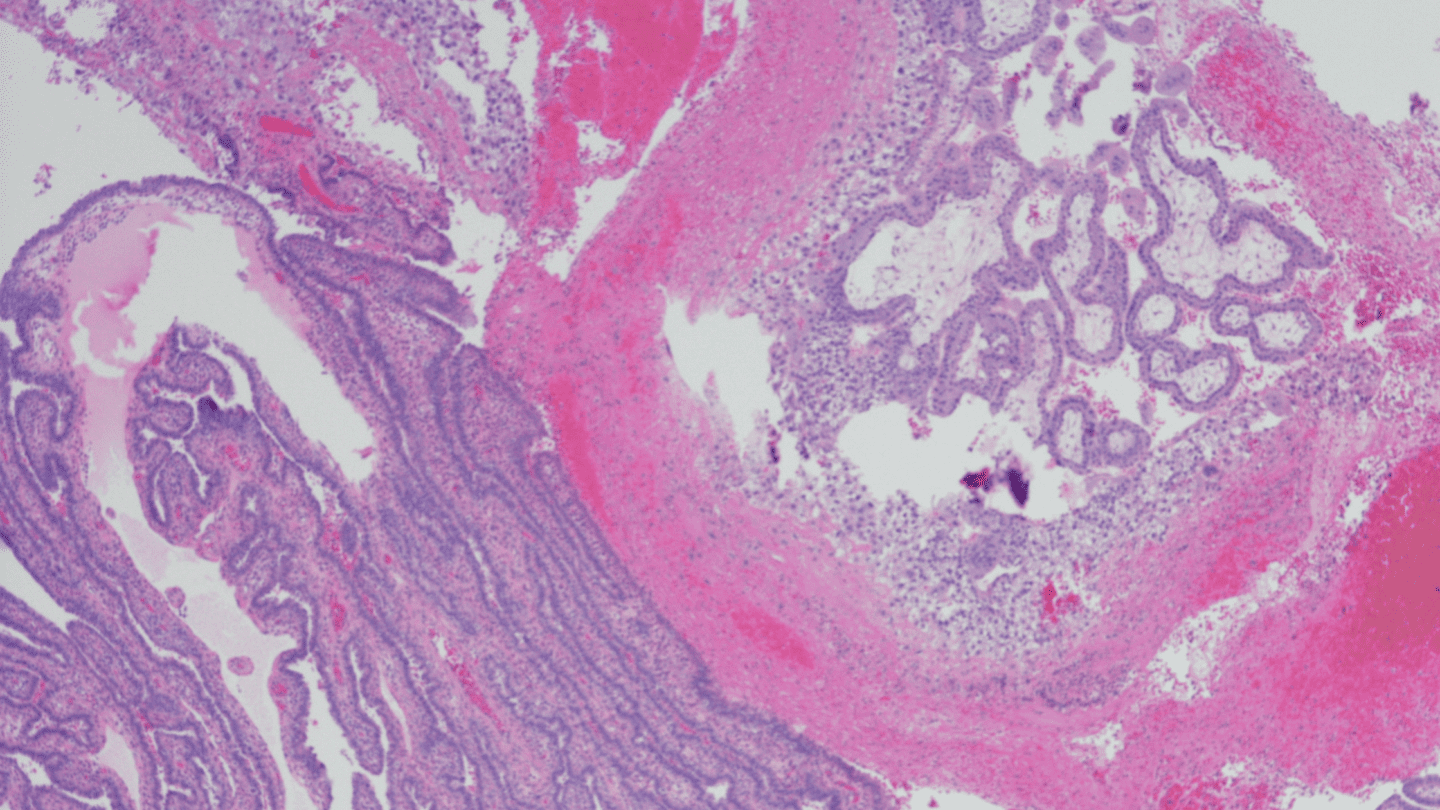

PCOS often creates fluid-filled sacs, or cysts, in your . These cysts overproduce certain sex hormones called s, which can lead to symptoms like acne and unwanted hair growth.1 But not everyone with PCOS develops these cysts, and some people will have cysts without having PCOS. The condition is complex, and the causes aren’t even completely known right now.1 But PCOS affects between 5-10% of people with who are of childbearing age, and it’s a common cause of .1

PCOS also usually occurs alongside increased resistance and weight gain. The connection means PCOS is often tied to additional health risks, like diabetes and cardiovascular problems.1 PCOS also often goes undiagnosed,1 so it’s worth discussing with your doctor if you have one or more PCOS symptoms that won’t go away.

Though PCOS symptoms can be frustrating and worrying, there are treatments available. is often prescribed to help with PCOS.2 The hormones in can decrease levels and help with many of the symptoms of PCOS.

What are the signs of PCOS?

Common PCOS symptoms include:3

- Excessive body hair, particularly on your face, chest, back, or stomach

- Irregular periods, very heavy, or very light periods

- Belly weight gain

- Bloating and cramps

- Difficulty getting pregnant or lack of ovulation

- Dark patches of skin or other skin abnormalities

- Pattern balding or scalp hair loss

Doctors now recognize that there is probably more than one kind of PCOS.4 PCOS is often diagnosed through higher-than-normal levels, ovarian cysts, and altered menstruation. But not everyone with PCOS has all of these symptoms. Recent research suggests that’s because there are a number of different biological mechanisms behind the disease.4 Other sex hormones like , ,5 and 6 seem to be altered in different forms of the condition, which can all result in different PCOS symptoms and outcomes for people.

With so much complexity, diagnosing PCOS isn’t straightforward. Your doctor will usually start by first eliminating other possibilities for your symptoms.1 Ultrasound is also usually used to check for ovarian cysts (though their presence or absence doesn’t necessarily mean you do or don’t have PCOS).

PCOS doesn’t always come with extreme or dangerous symptoms, but it can carry potentially harmful health impacts. In addition to diabetes, PCOS can lead to cardiovascular problems, high cholesterol levels, and increase your risk of endometrial cancer.1

What causes PCOS?

Scientists don’t know what causes PCOS right now, though researchers are studying it. There’s likely a strong genetic component,7 meaning you inherit risk from your parents, though genetics is just one factor. Being overweight and having diabetes are also risk factors.1,8

What we do know is that people with PCOS often have too many hormones and are often resistant to . Scientists believe that resistance usually comes first and leads to excess s, though there are likely additional complexities.8

Insulin is a that regulates blood sugar. Your body typically produces it in response to increasing blood glucose levels, which lets your cells access energy. resistance happens when your body can no longer use like it should, which can lead to diabetes.9 resistance can also increase belly fat – a common experience for some people with PCOS.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

How does this tie back to PCOS? Scientists suspect that with PCOS, resistance likely disrupts certain sex hormones that help regulate your menstrual cycle, leading to issues like irregular periods and abnormal bleeding. This disruption prevents the release of eggs from your ovary and causes cysts to form, which produce s.8

Androgens interact with other sex hormones in your body and are involved in regulating the menstrual cycle, conception, and pregnancy.10 They’re also responsible for symptoms of PCOS like excess hair, acne, and skin problems.1

Treatments for PCOS

There is no single treatment for PCOS, and treatments can vary depending on your symptoms and your overall health.11-12 Treatments for PCOS often include hormonal birth control, diabetes medications like metformin that treat resistance, high cholesterol drugs like statins, and blood pressure medications. In some cases, diet and exercise can also help.1

Is adyn right for you? Take the quiz.

Can cure PCOS?

Hormonal can help normalize levels, specifically by decreasing too-high levels which can cause many of the symptoms of PCOS .12-13 Many of the s used in decrease the production of s.12 So, doctors could prescribe a combined hormonal contraceptive like the combined pill or patch to help reduce your PCOS symptoms.

One thing to note is that options can have different kinds of s, some of which are more androgenic than others. The best options for PCOS might include the s drospirenone, norethindrone, desogestrel, dienogest, and norgestimate, all of which are less androgenic than some other types of s.13

Can you get pregnant with PCOS?

You can still get pregnant if you have PCOS, though it may be more difficult, and it can increase the risks to both the mother and the baby.1

One study of pregnancy and PCOS looked at over 3,700 pregnant people with the condition. Researchers found that 14% of mothers used assisted reproductive technology, versus just 1.5% of people without.14 That same study also found people with PCOS were more likely to experience pre-eclampsia – dangerously high blood pressure during a pregnancy – and gestational diabetes. They were also more likely to have very preterm births. That’s not to say you can’t have a healthy pregnancy if you do have PCOS. Don’t be afraid to talk to your doctor throughout your pregnancy so you can proactively monitor your health and get the best care possible.

What to do if you think you have PCOS

The symptoms of PCOS are broad, and they’re also not always present in everyone. Just because you have one or more symptoms of PCOS doesn’t mean you have the condition. But if you’re experiencing PCOS symptoms and you’ve been unable to figure out why, it might be worth asking your doctor if further testing is worth it, especially because the condition can occur alongside things like cardiovascular issues and diabetes. Doctors can request an ultrasound or additional tests that could help diagnose PCOS or rule it out.

If you do have PCOS, it can be worth exploring whether an option like can alleviate your symptoms. Learn how adyn can help.

-

- Norman, R. J., Wu, R., & Stankiewicz, M. T. (2004). 4: Polycystic ovary syndrome. The Medical journal of Australia, 180(3), 132–137. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb05838.x

- Badawy, A., & Elnashar, A. (2011). Treatment options for polycystic ovary syndrome. International journal of women’s health, 3, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S11304

- Office on Women’s Health. (Updated Feb 2022.) Polycystic ovary syndrome. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/polycystic-ovary-syndrome

- Głuszak, O., Stopińska-Głuszak, U., Glinicki, P., Kapuścińska, R., Snochowska, H., Zgliczyński, W., & Dębski, R. (2012). Phenotype and metabolic disorders in polycystic ovary syndrome. ISRN endocrinology, 2012, 569862. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/569862

- Guastella, E., Longo, R. A., & Carmina, E. (2010). Clinical and endocrine characteristics of the main polycystic ovary syndrome phenotypes. Fertility and sterility, 94(6), 2197–2201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.014

- Dumont, A., Robin, G., Catteau-Jonard, S., & Dewailly, D. (2015). Role of Anti-Müllerian Hormone in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: a review. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E, 13, 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-015-0134-9

- Vink, J. M., Sadrzadeh, S., Lambalk, C. B., & Boomsma, D. I. (2006). Heritability of polycystic ovary syndrome in a Dutch twin-family study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 91(6), 2100–2104. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2005-1494

- Rojas, J., Chávez, M., Olivar, L., Rojas, M., Morillo, J., Mejías, J., Calvo, M., & Bermúdez, V. (2014). Polycystic ovary syndrome, insulin resistance, and obesity: navigating the pathophysiologic labyrinth. International journal of reproductive medicine, 2014, 719050. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/719050

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Updated May 2024). About Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/insulin-resistance-type-2-diabetes.html

- Krüger, T. H. C., Leeners, B., Tronci, E., Mancini, T., Ille, F., Egli, M., Engler, H., Röblitz, S., Frieling, H., Sinke, C., & Jahn, K. (2023). The androgen system across the menstrual cycle: Hormonal, (epi-)genetic and psychometric alterations. Physiology & behavior, 259, 114034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2022.114034

- Carmina E. (2014). Polycystic ovary syndrome: metabolic consequences and long-term management. Scandinavian journal of clinical and laboratory investigation. Supplementum, 244, 23–26. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365513.2014.936676. Full text: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.3109/00365513.2014.936676

- Singh, S., Pal, N., Shubham, S., Sarma, D. K., Verma, V., Marotta, F., & Kumar, M. (2023). Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Etiology, Current Management, and Future Therapeutics. Journal of clinical medicine, 12(4), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041454

- Badawy, A., & Elnashar, A. (2011). Treatment options for polycystic ovary syndrome. International journal of women’s health, 3, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S11304

- Roos, N., Kieler, H., Sahlin, L., Ekman-Ordeberg, G., Falconer, H., & Stephansson, O. (2011). Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: population based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 343, d6309. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d6309