Updated October 14, 2024

Many of us have had that discussion with a friend or family member about how a given method didn’t work for them, while someone else will swear by that same method. Maybe your best friend had a bad experience with the pill and has sworn off hormonal birth control, but you can’t imagine using anything else.

Given that there are nearly 200 options in the US,1 it’s not surprising that choosing the right is incredibly hard and confusing, with plenty of conflicting advice. And unfortunately, given the research medical gap2,3 (and the namesake of our blog!) that has not adequately prioritized research into individualized choice, there is not a lot of evidence-based science that can clearly answer which is best for a given individual. As is often the case, this leaves the door open for a lot of pseudoscience that forces people seeking to rely on word-of-mouth and trial-and-error.

At adyn, our goal is to bring you our scientific perspective and clarity to this topic. It’s incredibly important, as can have awful side effects, ranging from acne to life-threatening blood clots.4 Let’s start by outlining the types of s currently approved and available in the US.

What types of are available?

Birth control methods can be divided into two categories: hormonal and non-hormonal.1 includes barrier methods such as male and female condoms or diaphragms, and other methods such as the copper (IUD) or the recently FDA approved non-hormonal vaginal gel Phexxi.

Hormonal methods constitute the majority of methods, including the following:

- Implant

- Shot

- Hormonal IUD

- Combination pill

- Minipill

- Patch

- Vaginal ring

Next we’ll go over the different types of options and specifically cover what they contain, how they work, and how they are delivered.

Let’s start by reviewing a few scientific terms that come up a lot when discussing .

Scientific Terms

Scientific Terms

- Hormones. A is a chemical signal that your body uses as a messenger to coordinate biological processes throughout your body.5 For example, you’ve probably heard of , a that plays a variety of roles in the menstrual cycle and in reproduction, including coordinating the preparation of the for pregnancy.

- Progestins. A is a synthetic (i.e. scientist-made) version of .4 A progestin is present in every type of . The primary contraceptive effects of s are:

-

- The prevention of ovulation (the release of an egg from your ovary — without an egg for the sperm to fertilize, you can’t become pregnant)

- Thickening of the mucus secreted by your cervix, which acts as a barrier and stops the sperm from reaching and fertilizing the egg.

-

- Estrogens. s are a type of that plays a role in reproductive development, the regulation of the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and lactation5. in is primarily present to help regulate bleeding, though it also prevents ovulation.4

Learn more about important hormones and their functions.

All methods include a , and some include an , as well. The methods work by delivering these biological signals to your body. Beyond their roles in reproduction, these types of hormones can also play roles in other biological processes in your body, including roles relating to body weight regulation, bone health, mood, and blood clotting. This is why methods can sometimes have unwanted side effects.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

Delivery methods

The biggest and most noticeable difference among methods is how the hormones are delivered to your body. A wide variety of options are available, and the delivery system can make a difference both in terms of efficacy and side effects, as well as your personal preference.

The Implant (Nexplanon). The implant is a small rod, about the size of a matchstick, that is inserted under the skin in your upper arm and releases a . It’s more than 99% effective, meaning fewer than 1 out of 100 people using the implant become pregnant per year of use. For most people, it will also lead to lighter periods. You only have to get it replaced every 5 years.

The Shot (Depo-Provera). The shot is an injection of a every 3 months. While it’s nice that you only do it once in a while, getting pricked isn’t for everyone, and visiting a provider every 3 months might not be possible/feasible for everyone. About half the people who use this method will stop getting their period while they are on the shot.

Though it is technically 99% effective, the reality is that we are all human, and not everyone is able to get to their 3 month appointment. So in reality, it is 94% effective (meaning 6 out of every 100 shot users will get pregnant each year of use).

One important caveat about this method: it can take up to 10 months after stopping the shot to get pregnant.

The Hormonal (Hormonal IUD; Mirena, Kyleena, Liletta, and Skyla). The hormonal IUD is a T-shaped piece of plastic that is inserted through your cervix into your , where it releases a . Depending on the brand, it can last between 3 (Skyla) to 7 (Mirena, Liletta) years.

The hormonal IUDs usually make your periods much lighter, and some people stop getting their periods altogether. All hormonal IUDs are 99% effective (meaning 1 out of every 100 hormonal IUD users will get pregnant each year of use).

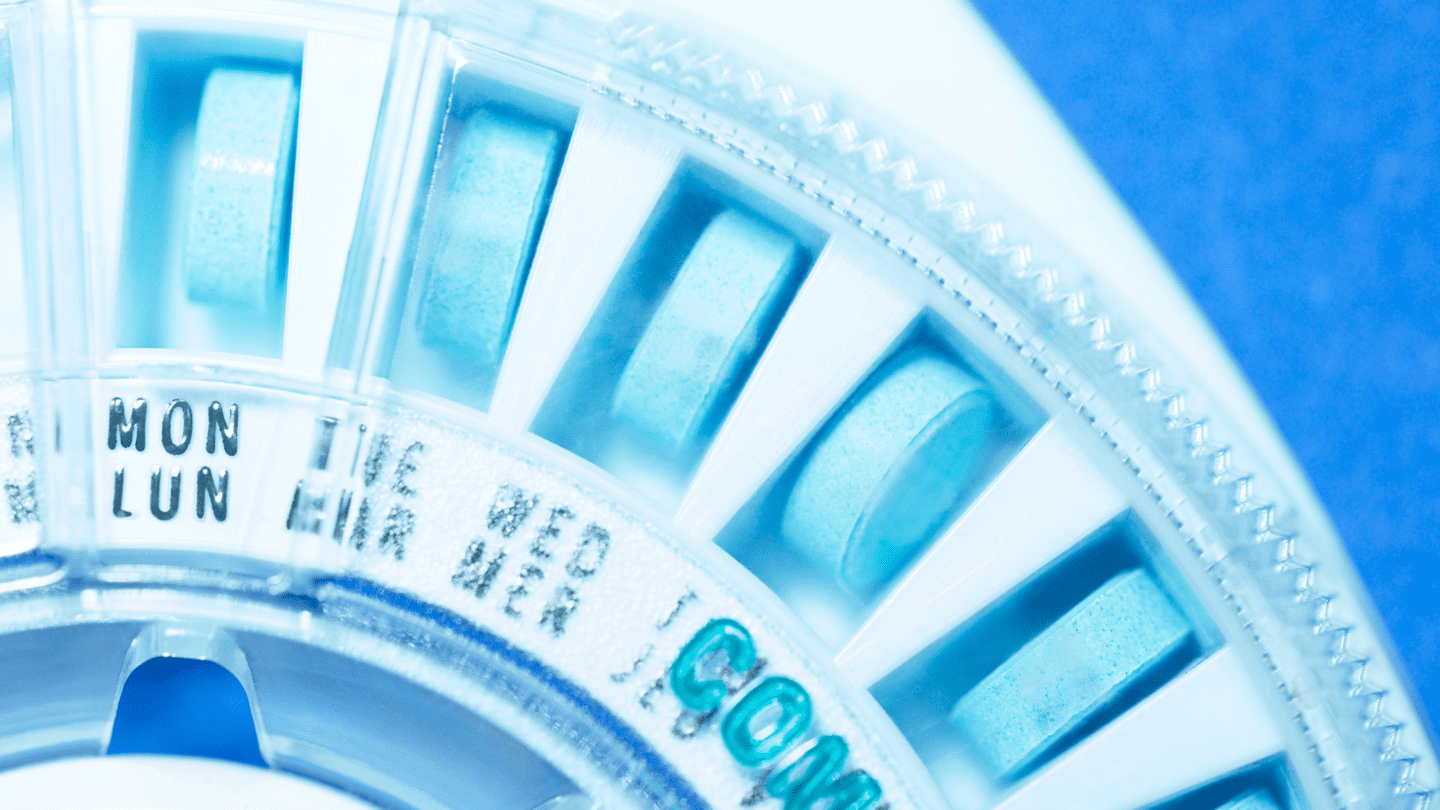

Oral contraceptives. Oral contraceptives are pills that are taken every day and contain either a alone () or a with an (combination pill). The pill will usually make your period lighter and more regular. You can even use the combination pill to safely skip your period, though this should be done in consultation with your doctor. Some pills are even specifically designed to provide longer cycles, up to three months in duration.

We’ll cover the main differences between the combination pill and in the next section, but they are both 99% effective if taken correctly. Though, as we’re all human, the real efficacy is 91% (meaning 9 out of every 100 pill users will get pregnant each year of use).

The Patch (Xulane). The patch is an adhesive patch that you can wear on your arm, belly, back or butt. It needs to be replaced once a week. The patch contains both an and a , which are absorbed through your skin and into your bloodstream. The patch will usually make your periods lighter and more regular. You can also opt to skip your period altogether if that’s your preference, though this should be done in consultation with your doctor.

The patch is 99% effective if used as prescribed, but as with other methods, not everyone is going to use it correctly all the time, so the reality is that it is effective 91% of the time (meaning 9 out of every 100 patch users will get pregnant each year of use).

The Vaginal Ring (NuvaRing, Annovera). The ring is a small and flexible ring that you wear inside your . In contrast to the IUD, which is inserted by a healthcare provider, you can insert the ring yourself. The ring contains an and a which are absorbed into your body through your vaginal lining. It needs to be removed every 3-5 weeks, and is left out for 1 week during which you will usually get your period. The NuvaRing needs to be replaced with a new ring, while the Annovera can be reinserted and lasts for up to a year.

The ring will usually make your periods lighter and more regular. You can also opt to skip your period altogether if that’s your preference, though this should be done in consultation with your doctor. The NuvaRing is 99% effective if used as prescribed, but the real efficacy of the NuvaRing is 91% (meaning 9 out of every 100 ring users will get pregnant each year of use).

The Annovera’s efficacy when used as prescribed is 97%.7 As Annovera is relatively new (it was approved in August 20188) there have not been enough scientific studies published yet for us to know the real efficacy. Here’s more on birth control rings.

Oral Contraceptives

A wide variety of oral contraceptives are available. The only contains a that is delivered at a low dose right at the threshold of efficacy4 (this is why it must be taken at the same time every day!). Despite this, the typical failure rate of progestin-only pills is similar to that of the combination pill.

Combination pills (commonly known as “the pill”) include both a and an . s can help inhibit ovulation, but their primary function in is to help regulate bleeding. Unfortunately though, s have been associated with some severe side effects in some cases, such as blood clots, so it may not be for everyone.

Different combination pills will also use different s (remember, is a type of , but there are different s that can be used in contraceptives) and different amounts of in a given pill. And while generic and brand-name drugs are marketed as interchangeable, it has been recognized that even pills that have the same active ingredients don’t always act the same.9

In short, there are A LOT of options – over 200 to choose from. Given that people use for an average of 30 years10, this is a choice that can drastically affect your health and wellbeing.

So what’s the best way to choose your ? Read on.

-

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Birth Control Methods. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/.

2. Kim, A. M., Tingen, C. M. & Woodruff, T. K. Sex bias in trials and treatment must end. Nature 465, 688–689 (2010).

3. Prakash, V. S., Mansukhani, N. A., Helenowski, I. B., Woodruff, T. K. & Kibbe, M. R. Sex Bias in Interventional Clinical Trials. J Women’s Heal 27, 1342–1348 (2018).

4. Horvath, S., Schreiber, C. A. & Sonalkar, S. Contraception. in Endotext (eds. Feingold, K. R. et al.) (MDText.com, Inc., 2000).

5. Hiller-Sturmhöfel, S. & Bartke, A. The endocrine system: an overview. Alcohol Heal Res World 22, 153–64 (1998).

6. Planned Parenthood Federation of America. Birth Control Methods & Options. https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/birth-control.

7. Archer, D. F. et al. Efficacy of the 1-year (13-cycle) segesterone acetate and ethinylestradiol contraceptive vaginal system: results of two multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 3 trials. Lancet Global Heal 7, e1054–e1064 (2019).

8. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new vaginal ring for one year of birth control. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-vaginal-ring-one-year-birth-control.

9. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 375: Brand Versus Generic Oral Contraceptives. Obstetrics Gynecol 110, 447–448 (2007).

10. Asai, Y. et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis in multiple populations identifies new loci for peanut allergy and establishes C11orf30/EMSY as a genetic risk factor for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immun 141, 991–1001 (2018).

11. Mohllajee, A. P., Curtis, K. M., Martins, S. L. & Peterson, H. B. Does use of hormonal contraceptives among women with thrombogenic mutations increase their risk of venous thromboembolism? A systematic review. Contraception 73, 166–178 (2006).

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/mmwr/mec/summary.html.