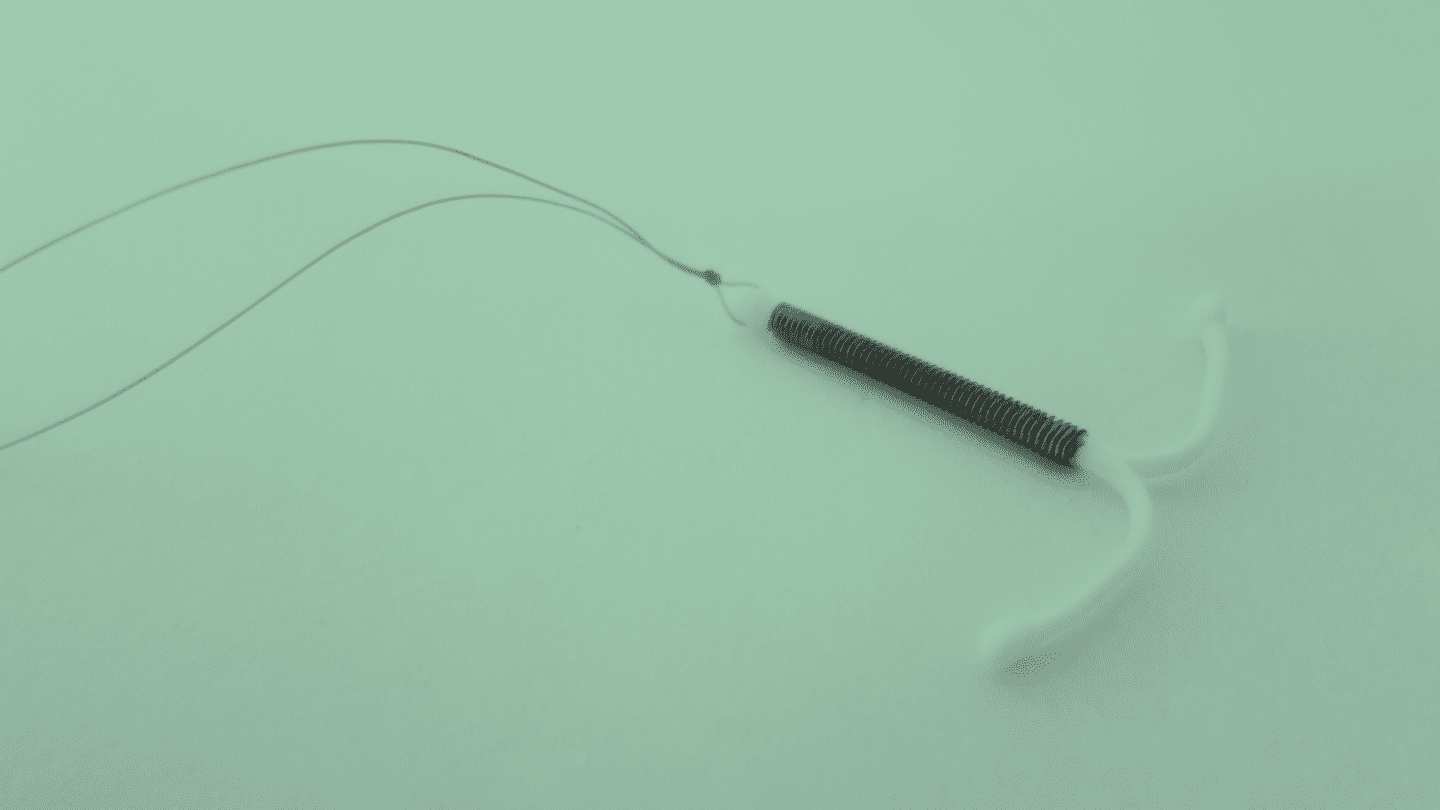

Like too many women, I’ve had my share of harrowing experiences. Back when I got an IUD in my early twenties, I had a seizure while it was being inserted. When I came to, the trash can had been knocked over and medical instruments were strewn about the floor. But for whatever reason, the medical professionals decided to continue the procedure after I began seizing. I wouldn’t learn until later – after a YEAR of pain during sex – that they had inserted my IUD incorrectly. That’s not my only bad experience. There was the ring I had in college that elicited a crippling depression. After two weeks of refusing to get out of bed, my sister yelled at me over the phone: “Take that thing out of your body!”

My personal experiences aren’t the only reason that I began to contribute to adyn, but they are a history that I carry with me every time I write a post for adyn’s blog Mind the Gap, or edit and fact-check posts authored by other blog contributors. When I was working on an article about the history of the IUD – which is wild and fascinating – of course I thought about my own IUD experience. There’s a myth of objectivity that pervades so much of traditional journalism, the idea that the writer can exist in some magical realm outside of reality as they write about it, applying a godlike lens to the trials and tribulations of the mortals. But the world doesn’t work like that, humans don’t work like that, and that’s why we at adyn thought it’d be helpful to pull back the curtain on the process of creating posts for our blog. Because we are real flesh and blood humans, we have histories, and we carry them with us in the stories we share with you.

The birth of blog posts

Blog posts emerge in all sorts of ways. We get ideas from the news, social media, our personal experiences, conversations among staff on our lively Slack channels, and analysis of what birth control-related questions people are searching for most often on Google. But the underlying aim is for the information we share to always be useful, accessible, and accurate. So let me go back to the IUD article as an example of what this looks like, in practice.

I came up with the idea for this article after going down a late night internet wormhole. I was reading an article that mentioned the Dalkon Shield, and had never heard of it. The Dalkon Shield was a notorious IUD that was prescribed to millions of women in the early 1970s and then caused a wave of horrifying health conditions, in thousands, and even death. It prompted more than 200,000 people to file suit in one of the largest tort cases in U.S. history. The device was so bad that the FDA changed the rules for FDA approval in response to the debacle. So how had I never heard of it before? I couldn’t believe it: how could a device that had such a huge impact on a generation now be largely erased from public memory?

“I couldn’t believe it: how could a device that had such a huge impact on a generation now be largely erased from public memory?”

The Dalkon Shield is a prime example of the problems that plague women’s health care innovation more broadly. It was put on the market with no large-scale clinical trials and limited federal oversight. Then, after it turned out to be a dangerous catastrophe because of a design flaw, you would think researchers would work to fix the problem, because clearly there was demand for IUDs. But no – instead, by the early 1980s there was only one IUD left on U.S. markets. The response to a problem wasn’t further innovation and research, it was to shut it down altogether. So even though American women could have benefited from long-acting reversible contraceptives like IUDs during the 80s and 90s, instead they’ve only made a resurgence in the past twenty years, with a long pause in development following the Dalkon Shield disaster.

adyn’s blog is called Mind the Gap in reference to the medical research gaps in knowledge when it comes to gender and race, where white men have received a disproportionate focus in medical research that bears very real consequences for women and people of color. We think the way to close these gaps is not only by increasing the inclusivity of scientific research, but also by drawing attention to the real world impacts that this research gap has had. This is why people really should know about the Dalkon Shield, and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and the countless other ways that racism and sexism have shaped our healthcare system, privileging some bodies over others.

Fact-checking reproductive health care history is a wild ride

When I write a blog post and when I edit other people’s blog posts, I always fact check any factual information that’s presented. I used to do this at a news outlet that I worked for, and it’s been a wild ride to see how many inaccuracies get published when it comes to reproductive health care, and how downright sloppy some outlets can be, even the ones you think are reputable. Let’s stick with the IUD blog post to illustrate this.

I was reading up on the history of IUD innovation and came upon a reference to an American scientist, Dr. Mary Halton, who had worked in the 1920s and 1930s to design and test IUDs. I thought, “How cool! A pioneering woman scientist leading the way in IUD innovation in the early 20th century, it shouldn’t be too hard to find information about her, right?” Wrong! This article from the Reproductive Health Access Project about the history of the IUD seemed reliable enough, and they said, “In 1949, however, Dr. Mary Halton was back at work describing the use of silkworm gut [for IUDs].” But I tracked down Halton’s obituary, and it turned out that she had died in 1948, so she couldn’t have possibly been making IUDs out of silkworm guts in 1949. Turns out that the article they were referencing was published in 1949, after Halton had died. Another article about Halton said she was designing IUDs in the 1950s, clearly her ghost had been very busy.

Another fact I checked that was a bit murky was the question of how many people had actually gotten the Dalkon Shield during the time it was on the market. TIME Magazine published an article in 2015 claiming that three million women had used IUDs, citing an article TIME had published in 1974 as their source. But if you read the 1974 article, it actually says that two million women used IUDs, a million person error. Other outlets then picked up the three million number, assuming that TIME Magazine had been adequately fact-checked to report it. A more widely cited number, including by a number of academic journals, and the one we went with at adyn, is that 2.2 million women were prescribed the Dalkon Shield. But some outlets also published that the number was 2.5 million – the New York Times published one article in 1987 claiming it had been prescribed to 2.5 million women, and another in 1996 claiming it was 2.2 million.

This is all to say that fact checking is not always straight-forward, and sometimes we have to make a judgment call based on scanning all available information to determine what seems the most accurate, or most verifiable. Even major national outlets like TIME Magazine and the New York Times get it wrong sometimes.

Being a person while writing a blog post

My intention in giving you all that information about the process of fact-checking a blog post isn’t to say, “Hey, look how great we are that we caught those errors,” but rather to draw your attention to the fact that all the written material you encounter on the internet is created by real people, who sometimes make mistakes and who often are doing the best they can with the resources available to them. And that any information you encounter is a result of a number of choices somebody made, based on what is important to them, and what they think is likely important to you, the reader they are imagining as they write.

“Any information you encounter is a result of a number of choices somebody made, based on what is important to them, and what they think is likely important to you, the reader they are imagining as they write.”

When I was writing the blog post about IUD history, even though I was thinking about my own awful IUD experience, and perhaps that experience is part of what got me so fired up to write the post in the first place, I didn’t actually mention any of that in the piece. The tricky part about writing with authority is that we often don’t want to draw attention to our subjectivities – the way our humanity informs how we process information about the world. But they are there, and can seep through in subtle ways, like by determining which issues we choose to focus on, and which we don’t. Representation and inclusivity are so important in the medical field. We need more written material exploring the stories of reproductive health care and medical issues that differentially affect people with uteruses.

The truth is that even in the course of writing this blog post, I got an idea for another blog post about the history of empiricism, and how we humans came to define much of our existence through a set of binaries: mind/body, male/female, logic/emotion, objective/subjective. These underlying presumptions about the way the world works are everywhere, and have very real consequences on our lives. But I’ll leave that behemoth for another day, and close by saying thank you so much for reading, and hi, it’s nice to meet you. It’s time for me to go make some lunch, and then I have another writing task for adyn to get started on. I’m a real person, and I wrote this article.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌