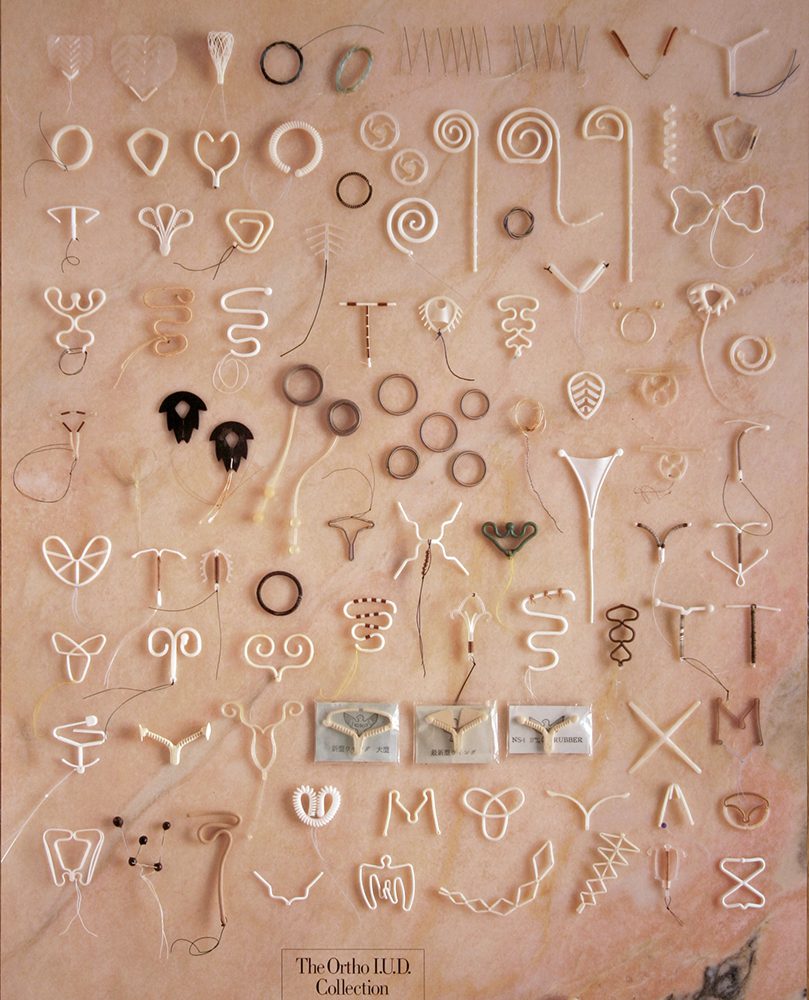

Humans have long had the brilliant idea of putting foreign objects inside the as a way to prevent pregnancy. What could go wrong? Well, a lot. Although intrauterine devices (commonly referred to as IUDs) are incredibly safe now, it wasn’t always that way. The road has been rocky, to say the least.

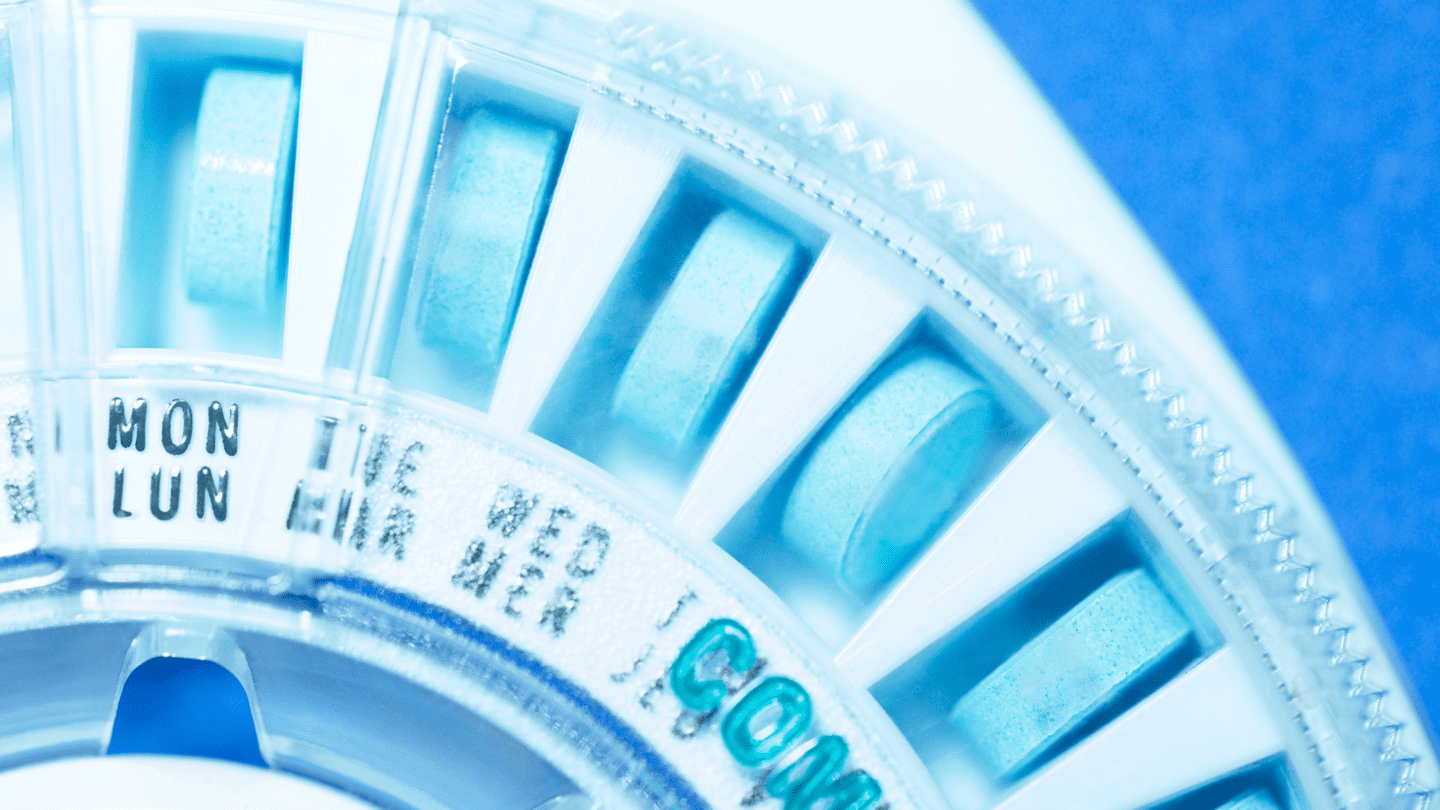

Today, IUDs are among the most effective types of , and are a form of long-acting reversible . They are small T-shaped devices that are inserted into the by a medical professional during a procedure that is fairly quick but can be painful. IUDs are effective for between three and ten years, depending on the type, and there are both hormonal and non-hormonal IUDs on the market. This is a far cry from the IUDs of the past.

From inserting silkworm guts, to turning women’s gums blue from putting pure silver into their uteruses, IUDs have taken on a number of iterations over the years. Let’s take a journey back in time to the IUD’s bizarre beginnings, through the tidal wave of lawsuits in the 70’s and 80’s, and see how we got to where we are today.

The Early Days: Silkworm Guts and Experimentation

Intrauterine devices were not a viable option before the twentieth century and the dawn of modern medicine, despite myths on the internet about pebbles being inserted various places to prevent pregnancy. In 1909 the first IUD design was published by Dr. Richard Richter, involving strands of silkworm guts that he obtained by killing the worm just as it was ready to spin its cocoon. By the 1920s, the German scientist and physician Ernst Gräfenberg (better known as the namesake of the G-spot), had reconfigured Richter’s design into a ring shaped device that would become widely used throughout Great Britain, Canada and Australia in the following decade.

Gräfenberg’s ring contained an alloy of copper, nickel and zinc – he first tried using pure silver for the ring, but found that it caused women’s gums to turn an unbecoming shade of bluish-black. Gräfenberg’s ring was popular for a reason: he reported at a conference in 1930 that out of 600 women, less than 2% became pregnant while using it. But it wasn’t exactly safe – as the IUD grew in popularity, so did reports of pelvic inflammatory disease linked to it.

Is adyn right for you? Take the quiz.

During that same period, American gynecologist Dr. Mary Halton was studying IUDs created with silver, gold, and silk, but she had difficulty getting her findings published in American medical journals: the U.S. gynecological community was resistant to IUDs as a mode of . When Gräfenberg emigrated to the U.S. during World War II – he was the first male gynecologist at Margaret Sanger’s Clinic – he ended up shifting his focus away from IUDs because of controversy associated with the method, despite previous successes with his design. Instead, Gräfenberg spent the rest of his life studying cervical caps and diaphragms in his contraceptive work. In Europe too, IUD progress was stalled during the World War II era, amid pressures by the Nazi regime and other nations to ban and encourage the populace to make lots of babies.

The Infamous Dalkon Shield

Things started to change for IUDs in the 1950s and 60s, as the world fell in love with the magic of PLASTIC. American physician Dr. Lazar Margulies designed a coiled polyethylene IUD in the late 1950s that he first tested on his wife, known as the Margulies Spiral; it went on the market in 1960. Another plastic IUD, The Lippes Loop, was first introduced in 1962, and soon became the most widely used IUD in America. Things were looking up for IUDs! Consumer confidence was growing, as was faith in the medical community that IUDs were an increasingly safe and effective option. Then came the Dalkon Shield.

In the 1970s, nearly 10% of women using contraceptives in the U.S. had an IUD – by the 1990s, it was less than 1%. That dramatic drop can largely be attributed to the Dalkon Shield: a disastrous and deadly IUD that was prescribed to 2.2 million women in the first three years it was on the market. Rushed to market despite minimal clinical data, it had a major design flaw: a removal string that had the tendency to divert bacteria into the because it wasn’t sealed on either end. Part of why nobody caught this flaw before it was put into millions of women’s bodies was because there was almost no federal oversight or assessment of the Dalkon Shield before it went to market. That’s because it wasn’t classified as a drug – the Food and Drug Administration began regulating devices in 1976, after legislation was passed because of the Dalkon Shield catastrophe.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

The Dalkon Shield was eventually the subject of the largest tort case in U.S. history, with more than 200,000 claimants who suffered a host of horrifying health impacts, including: pelvic infection, septic infection, , ectopic pregnancy, uterine perforations, and spontaneous septic abortions. As of 1985, at least 21 women had died and 13,000 were either sterile or infertile because of using the Dalkon Shield. It was later revealed that the manufacturer knew about the design flaws of the Dalkon Shield as early as six months before it went on the market.

A Legacy of Distrust and Slow Resurgence

Even though there were 16 other IUD models on the market in the 1970s that did not have the problems that plagued the Dalkon Shield, the device’s notoriety had lasting negative impacts for public perception of IUDs. By 1986, there was only one IUD left on the market. Researchers found that OB-GYNs were not recommending IUDs to their patients in the late 80s, and a 1991 survey found that just 16% of U.S. women had a positive opinion of IUDs.

But in the early 2000s things began to change as hormonal IUDs like Mirena entered the market, with high effectiveness and minimal side effects. A 2012 study by the Guttmacher Institute found that IUD use nearly quadrupled between 2002 and 2009, up from 2.4% of contraceptives used in 2002 to 8.5% in 2009. Then, after former President Trump was elected in 2015, the drive for long-acting removable contraceptives (LARCs) like IUDs skyrocketed, likely due to widespread worries of losing contraceptive coverage. There was a 21.6% increase in demand for LARCs in the 30 days after the election! Confidence in IUDs among medical professionals also increased. A 2015 study found that female physicians who worked in family planning were more likely to use IUDs than any other form of .

The Politics of IUDs in a Post-Roe America

In recent years, some conservative lawmakers have worked to ban or restrict IUDs, conflating them with abortion – even though there is overwhelming scientific evidence that IUDs are contraceptives, not abortifacients. In 2014, the arts and crafts store Hobby Lobby fought to deny coverage of the IUD on religious grounds, claiming that IUDs are a form of abortifacient. The business was victorious in their efforts, and a Supreme Court ruling established that businesses can deny coverage of IUDs and certain other types of contraceptives on religious grounds. Since then, a number of states have gotten entangled in the debate over whether access to IUDs can be restricted, including Colorado, Missouri, and Montana, though no legislation has been passed that would limit access. While the number of Americans using IUDs continues to grow, whether access to IUDs will be restricted in a post-Roe world remains to be seen.