When I was in nursing school, we spent a few days of class discussing health policy and advocacy. I spent most of that time reviewing flashcards. I wasn’t a bad student — I thought I was doing what was best for my patients, studying so I could save their life, not worrying about silly policies I didn’t have control over. I knew our healthcare system was broken, that folks who have never touched a patient were making the rules guiding my practice. I didn’t care about policy, I was going to do whatever was best for my patient regardless of what the policy was.

I spent the first few years of my career doing just that, focused on what was best for the patients in front of me. Eventually, I left the Intensive Care Unit and worked in the Emergency Department. But I began to feel like every patient I saw was the result of a different policy failure: unaffordable housing or medications, patients not having time to take off from work to see a doctor, people without access to health insurance, asthma attacks because of the pollution near where the family lived, and hypothermia in people who didn’t have heat or a place to stay.

“I began to feel like every patient I saw was the result of a different policy failure”

I started looking beyond the initial complaint of the patient to understand how they ended up at the hospital. That was when I realized health policy wasn’t just what dictated how nurses or doctors practiced, it was all over the conditions shaping our health.

How does policy relate to health?

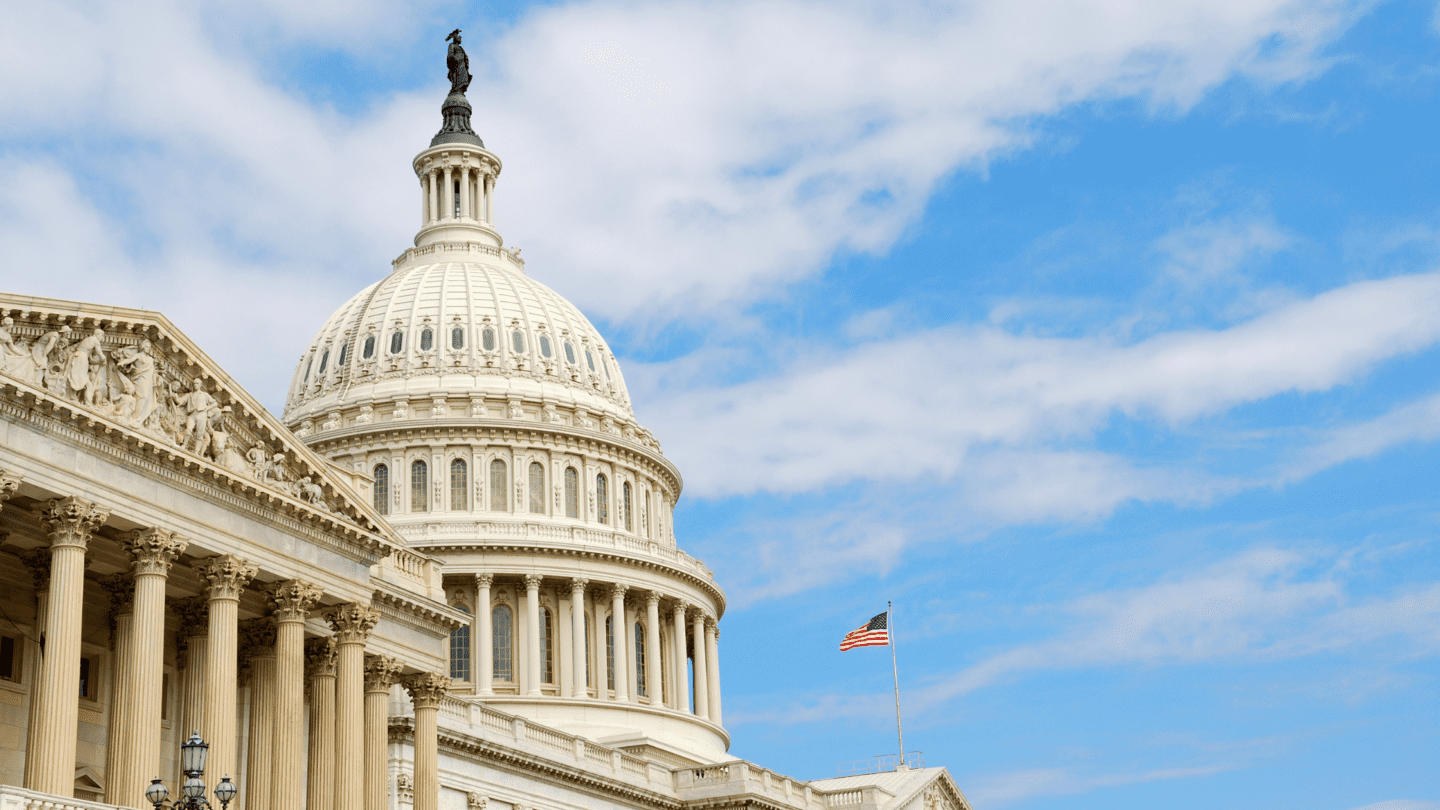

When we talk about health policy, we often think of “Medicare for All,” the “Affordable Care Act,” and more recently the push to cap prices at $35 per month. These are important aspects of health and address parts of our healthcare that need fixing, but they are not the only ways that policy shapes our health. We all intuitively know, and scientific evidence supports, that the social determinants of health – where we live, eat, learn and grow – directly impact our health. Policies advanced by lawmakers have wide-ranging impacts on the social determinants of health, which is why voting is so critical.

Is adyn right for you? Take the quiz.

Housing

Having stable and well maintained housing often makes the difference between ending up in the Emergency Room or being readmitted to the hospital. You can have Medicaid coverage, but if you don’t have a safe place to sleep each night, where you are protected from the elements and have a safe place to store medications, it is harder to prioritize your health; you are more likely to end up in the hospital.

And to have housing, you need to be able to afford housing. We know that the U.S. has an affordable housing problem. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines a person as “rent burdened” if they spend more than 30% of wages on rent, and “severely rent burdened” if they spend more than 50% of wages on rent. According to the US Census Bureau, in 2021, 51% of renters were cost burdened and out of that group, 26% of renters were severely cost burdened. Increased spending on rent leaves less left over for other necessities, including food and healthcare.

How did we end up in the housing crisis? Policy. We know people vote with their own self-interest in mind. The U.S. government created housing and tax policies, like The Mortgage Interest Deduction, that incentivize home ownership, using homeownership as an investment tool and a way to pass along generational wealth. On the surface, this policy seems benign, if not helpful – people should want to own a home, right? There is nothing wrong with owning a home! However, most residential areas are zoned for single-family homes, often with yard minimums and off street parking minimums. To deviate from these requirements, the builder must obtain a “variance,” usually from a local zoning board, which requires a public hearing.

This fosters an environment where homeowners vote to “protect their investment.” There is a fear that affordable housing (often multi-dwelling units like apartment buildings) will devalue current properties. Many of the decisions around affordable housing are made at zoning-board meetings. Decisions only get made when people turn up to make them. The fear of potential devaluation of their home and investments causes people to advocate against affordable housing and limits the amount of new affordable units that can be built.

It is not just current day housing policy that affects health.

Housing policy is rooted in racism. In 1934, the Federal Housing Authority adopted redlining practices, rating neighborhoods by the “riskiness of the loan.” How they defined risk was directly correlated with the housing conditions and in the neighborhoods. This system was used to deny mortgages to Black and other non-White, non-western European homebuyers, preventing Black families from buying homes in white suburbs and keeping Black families in urban housing projects. Not only did this increase the disparity in generational wealth between Black and White families, new research shows that living in historically redlined areas today is associated with increased risk of serious health outcomes.

Transportation

The policies shaping transportation access can have far-reaching impacts. For people without a car, access to public transportation limits where they can work and shop for groceries. Smaller corner stores generally have higher prices, and research shows predominantly Black and lower income neighborhoods have less available healthy foods. Limitations in transportation can force families to choose between paying more for groceries, or taking taxis or walking significantly farther to purchase food.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

In Boston, MA, Mayor Wu recently eliminated fares on certain bus lines, and added two more bus routes in lower income areas. The change allows the city to address equity and analyze ridership. “Lower transportation costs will put money back into the pockets of riders while leading to many other intangible benefits, like improved air quality––particularly important in these communities, which have higher than average asthma rates,” said Mela Bush Miles, the director of the city’s transit development department.

Additionally, policies like Boston’s allow for greater flexibility in all aspects of life. We often think of these high profile federal policies as having the highest impact on health, but we’re seeing more and more examples of local elections creating important change to improve health.

Voting access

Voter ID laws, voting access and gerrymandering disenfranchise non-white, underrepresented minorities and help white upper class folks who are able to take time off to vote. Politicians know that to be re-elected, they must create policies, fight, and vote for policies that their constituents want. In lieu of following their constituents’ wishes, many have turned to making sure the people who are able to vote are the people who will vote for them.

One of the best examples of the correlation between policy and voting came after women gained the right to vote and the subsequent passage of the 1921 Sheppard-Towner Act, a significant five year public health investment that dramatically reduced the child mortality rate. This was not a popular bill within Congress, but it was with women. Voting habits of elected officials changed because they knew their constituents would know how they voted. After the vote, one Senator said, “If the members of Congress could have voted on the measure in their cloak rooms, it would have been killed as emphatically as it was finally passed out in the open.”

Voter suppression has also been codified in a number of ways. Thirty-five states have some form of Voter ID laws. Some are strict, requiring a government issued photo ID, others allow voters to vote on a provisional ballot and bring identification at a later date for the vote to be counted. There are systemic barriers that make obtaining government issued photo IDs harder for underrepresented minorities. One of the most interesting cases is that Texas allows voters to use handgun licenses as identification, but not a student ID. Texas is one of seven states that does not accept student IDs, among states requiring in-person voter ID. It is no coincidence that Texas has some of the most gun-friendly laws in the country.

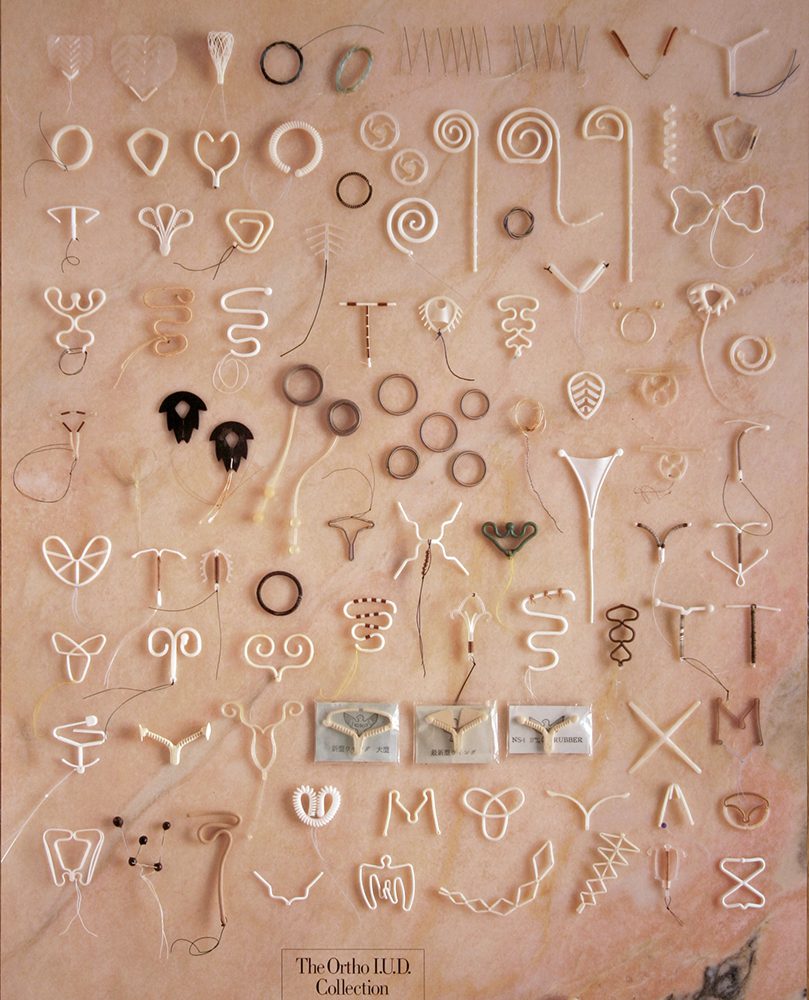

More directly, voter turnout affects ballot initiatives. Some initiatives have more local consequences, like nurse-patient staffing ratios or school budgets. In the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson, six states have ballot measures shaping abortion rights for their states in the upcoming election. Kansas already voted to protect abortion rights in their constitution via ballot measure. California, Kentucky, Michigan, Montana, and Vermont all have measures on the ballot for the November 8 midterm election impacting future abortion access.

Conclusion

The American novelist Alice Walker said, “The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don’t have any.”

It is easy to become disenchanted by our current political system.

It is easy to sit back and say, “My vote won’t matter.”

It is hard to take the first step, realize that you have valuable opinions and that you can change your health with the stroke of a pen.

Maybe you’re not worried about your health, and that’s fine! Think of someone you care about, your parents or siblings, your partners. I think of my nieces. I want them to grow up with the right to choose if and when to have children, to play outside and breathe clean air, and to have access to clean water and healthy food. I vote so that they never have their rights decided by a court decision.

Here is my ask: Check your voter registration. If you aren’t registered, REGISTER! If you are, ask one other person if they are registered to vote.

Naomi Fener is a NP, MPH. She obtained her nursing degree from Johns Hopkins University, her Nurse Practitioner degree from Vanderbilt University, and her Master’s in Public Health with a focus in Health Policy from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She has worked in healthcare since 2011 in intensive care, emergency medicine, and transitional care. In addition to working in the Intensive Care Unit at Mass General Hospital, she also works in health policy. She serves on the board of advisors for Vot-ER, a nonprofit organization that integrates voter registration into the healthcare delivery system. Naomi served on the White House Clinical Leaders in Round Table from 2021-2022.

Are you registered to vote? 🗳

Check your voter registration status with our partner Vot-ER.