I cried during my public health clinical rotation: “These patients aren’t sick.” Having spent the previous four years as an EMT, I knew my place was in the Intensive Care Unit, with the sickest of the sick. “These patients aren’t even in the hospital, they don’t need my help,” I thought. I wanted to be a nurse helping the patients who needed it most, and I thought that meant those in the Intensive Care Unit. Looking back now, I laugh at how wrong and naïve I was.

In nursing school, we learned about “whole person care.” We needed to make sure the patient didn’t have to walk up steps to get into the house, and knew not to take certain medication with grapefruit juice, and made sure if they’d fallen to ask about small pets or area rugs. But we didn’t learn about how drastically health insurance status affects health outcomes, or how not having stable housing increases your probability of being admitted to the emergency department. The only “cultural considerations” we were taught were related to end of life care, and stereotypes, like that Asian men tend to be stoic and may require more pain medication. I still remember the pharmacology textbook written by my instructor suggesting we tell African American patients their appointments were 15 minutes earlier than scheduled, because ‘African Americans are always late.’

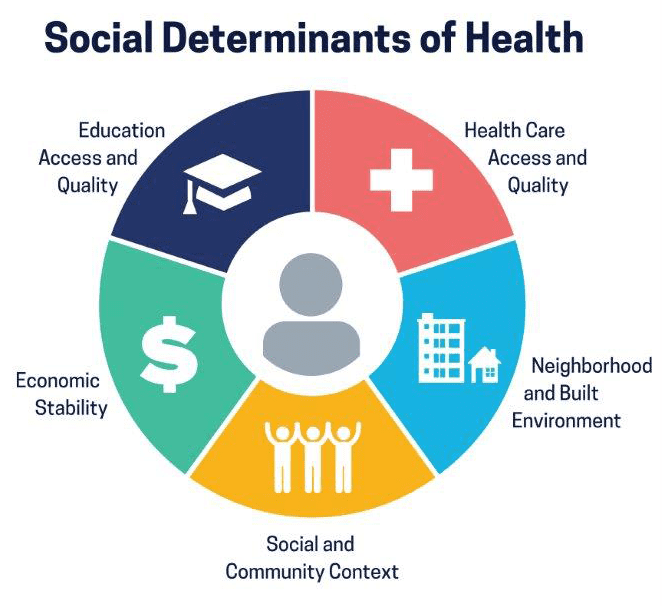

We didn’t learn about all the things outside of a person’s control that affect their health and how much more those factors can affect your health than medication your doctors prescribe. It took years of hearing patients’ stories for me to understand the immense significance of social determinants of health: how where you live, what food you have access to, your race, ethnicity and insurance status all affected your health status more than my actions as a nurse. Below, I’ll share some of my experiences to demonstrate what those social determinants of health look like in the real world.

When I finished nursing school, I started working in the Intensive Care Unit. I forgot all about my time in the public health clinic and focused solely on treating the patient in front of me. At the time, the only social history we cared about was which family members were able to visit and who the patient’s health care proxy was (the person making medical decisions for the patient if they were unable to make them for themselves.)

It didn’t matter what factors led them to the ICU, if they were preventable or not, or what insurance they had – we just did everything we could to save a life. After four years, I transferred to the Emergency Department, and suddenly all those social factors were staring at me during every shift. I got a crash course in the social determinants of health.

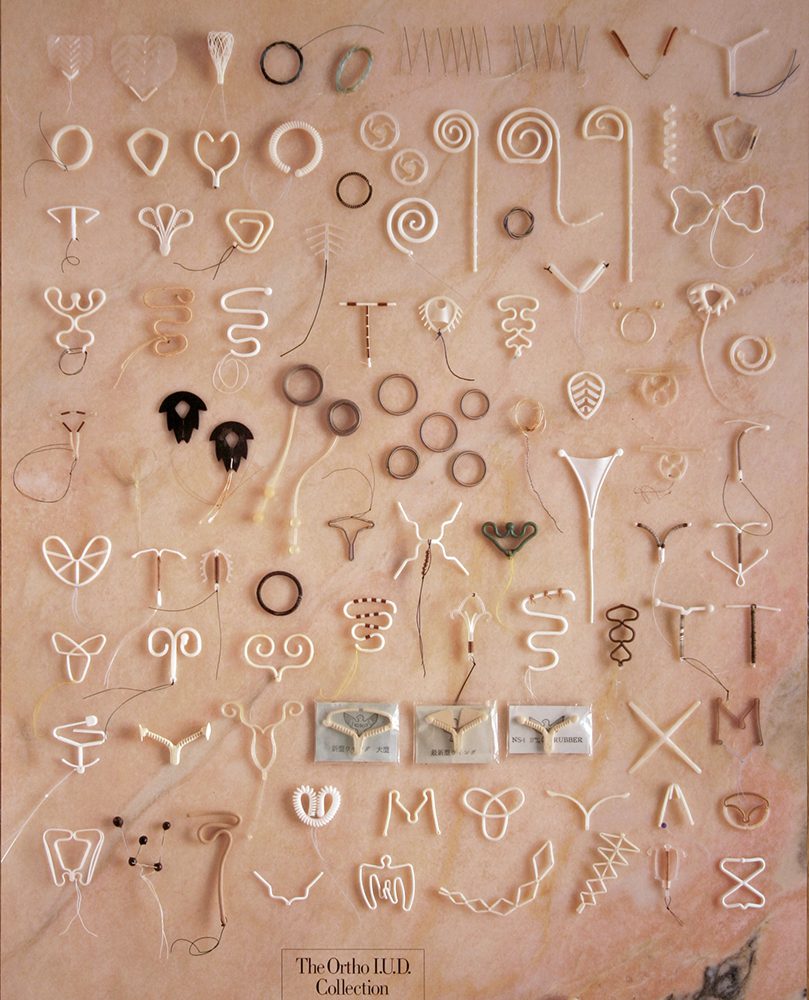

What are “Social Determinants of Health?”

Image Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health (SDoH) as “the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes.” We know them as the conditions of where we live, eat, learn, work, and play. Often, these factors are interrelated and compound on one another. Lower incomes can mean living in housing located in areas of cities with less access to public transportation or good schools. They might be in areas with more hazardous waste or pollution, or formerly redlined areas with a higher proportion of non-white people.

Where you live

When you go outside, do you have fresh air, reducing your risk of asthma and other respiratory diseases? Or is the pollution and smog so bad that sometimes you can’t even go outside? Are there trees around your street or parks close by that you can walk to? Recent studies have shown that as little as 15 minutes of walking can activate your sympathetic nervous system, decreasing heart rate and reducing anxiety.

Where you live can have a wide range of health impacts. These include things that many take for granted: a refrigerator to store certain medications safely, heating to reduce your risk of hypothermia, access to air conditioners or fans during heat waves, or proximity to grocery stores with fresh produce. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the U.S., we saw a phenomenon happen that public health researchers often cautioned about: crowded living spaces allowed infectious disease to spread more rapidly, putting people who lived in close quarters at greater risk of contracting the virus. Researchers have also found that substandard housing is linked to exposure to asthma triggers for low income children with asthma.

For my patients, it was the retiree who had a fixed income and couldn’t afford to pay for his new blood pressure medications. “But why weren’t you taking your medications?” I asked him.

His wife was startled: “I didn’t know you were supposed to be taking medications?” “They were just too expensive,” he replied. Others simply lacked the basics that many of us take for granted. One patient with diabetes arrived to the hospital in a coma because he didn’t have a refrigerator in which to store .

What you eat

Do you have time to not just cook your meals, but also to plan, shop and clean up, or do you have cheaper pre-prepared meals that are higher in sodium and fat? Researchers have found a strong link between poverty and food insecurity, and there are numerous adverse health implications of being food insecure, i.e. not having access to enough food that is healthy and nourishing. In adults, food insecurity is associated with higher rates of depression, diabetes, , and more. People of color are significantly more likely to be food insecure in the United States.

One of my first patients was a truck driver from rural Massachusetts. He never exercised and got most of his meals from gas stations. He suffered a massive heart attack, had no heart rhythm and was in our care for nearly six months. He required countless surgeries and multiple mechanical support devices to stay alive. Ultimately, he received a heart and kidney transplants. We spent well over a million dollars to save his life. He walked out of the hospital.

He survived a grueling time. But with moderate exercise and more appropriate dietary habits, it is likely his admission would have never happened.

Food access, income, housing, and race are deeply intertwined and there is a vast body of research delving into how important these factors are for influencing health.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

What your race is

The health impacts of structural racism are far-reaching. In addition to policies that directly cause the racial inequities we see in housing, wealth, education and other social factors, healthcare providers –myself included – have quite literally been taught racist medical practices and perpetuated stigma that guide our treatment. This country’s history of racism has led to continued racial disparities in housing and income. Only 6% of white households are extremely low-income renters, while 20% of Black households are extremely low income. Structural racism, and resultant lower wages, and has prevented Black families from accumulating wealth and passing down generation wealth through homeownership. Of all homeowners, 65% are white, and only 12% are Black.

Unscientific and racist beliefs directly impact patient care: ideas like Black people have thicker skin, need less pain medication, and the use of race in estimation of kidney function, leading to few Black patients receiving kidney transplants and Black birthing people dying at over 3 times the rate of white birthing people. Stories like those of Serena Williams after the birth of her daughter, knowing she had a life threatening pulmonary embolism, asking for help and being dismissed by her nurse are just one of many examples of the medical community treating Black patients differently, resulting in loss of trust in the medical community.

While there has been robust discussion among medical scholars and professionals of whether racism is a “root cause” versus a social determinant of health, the classification is far less relevant than the clear impact that racism has on health outcomes. We in the medical field need to take responsibility to improve , change our curriculums and advocate for policy change. Despite what many clinicians were taught in medical and nursing school, it is not the color of your skin that determines your kidney function, or amount of pain medication people need, racism does.

“Once you see them, you cannot unsee them”

With my nurse practitioner degree, I returned to the ICU, but this time with a profound awareness of social determinants of health. Once you see them, you cannot unsee them. Social determinants of health are everywhere. Recent studies demonstrate between 30 and 55% of our health is related to SDoH. The COVID-19 pandemic catapulted these factors into the forefront of healthcare, but because these factors are generally not taught in medical school, they are not discussed between providers and patients at appointments. Once I understood the impact that social determinants of health have on my patients – and myself – I pivoted my focus from critical care to addressing these factors on a larger scale through policy change.

For providers: Start asking your patients if they have a safe place to sleep, if they worry if they will have food to last the whole month and if they can afford to pay for their medications and to keep the electricity and heat on. The medications we prescribe are useless without all these things.

Not a provider? You can still help! Vote.

Naomi Fener is a NP, MPH. She obtained her nursing degree from Johns Hopkins University, her Nurse Practitioner degree from Vanderbilt University, and her Master’s in Public Health with a focus in Health Policy from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She has worked in healthcare since 2011 in intensive care, emergency medicine, and transitional care. In addition to working in the Intensive Care Unit at Mass General Hospital, she also works in health policy. She serves on the board of advisors for Vot-ER, a nonprofit organization that integrates voter registration into the healthcare delivery system. Naomi served on the White House Clinical Leaders in Round Table from 2021-2022.

Are you registered to vote? 🗳

Check your voter registration status with our partner Vot-ER.