When you’re using to prevent pregnancies, it’s absolutely critical to know how protected you really are. Every form of on the market comes with information about how effective it is, which is a key factor people should consider when comparing different options. Some differ by just a few percentage points — say, 98% effective versus 99% effective. But many people are surprised to learn how ineffective some contraceptive options are, like female condoms, which can be as little as 79% effective with typical use!

These odds aren’t just numbers; they can be life-changing. There are many reasons a person might want to avoid getting pregnant, whether the reasons are medical, financial, personal or something else entirely. And for many, abortion isn’t an option, either due to lack of access or personal conviction. That’s why the difference between 79% and 99% is so important.

At adyn, we’re here to connect people with the that works best for them — and that includes maximizing the probability that it’ll get its job done. No matter what kind of you opt for, it should be rated as “highly effective” — which we define as at least 98% effective at preventing pregnancy, assuming perfect use.

A number of options meet those standards. Of these, the best for you depends in part on your lifestyle, medical history and even your genetics. But before making any decisions, it’s worth unpacking some of the often confusing concepts surrounding effectiveness. For example, what’s “perfect use” anyway? And what does 98% effective really mean?

What effectiveness means

Contraceptives report their effectiveness, or the odds they’ll prevent pregnancy, as a percentage. It’s a common misconception that these numbers tell you the risk of getting pregnant after each time you have sex. They are an annual average. For example, an 80% effectiveness rating means 20 out of every 100 people using the contraceptive will get pregnant each year — that’s 1 in 5!

It’s also important to remember that reported averages are just that: averages. Even a that offers 99% effectiveness can’t guarantee that you won’t get pregnant, especially since your own unique biology can affect how well a certain method works for you. Research into which factors might change effectiveness is still relatively new and ongoing, but new evidence has already suggested a few factors that might have an impact.

For instance, researchers are learning how body size can influence the concentration of hormonal contraceptives in the body (it seems obvious, doesn’t it?). A study in 2019 found that people who had a higher body-mass index and who had used hormone-releasing arm implants for longer periods of time had lower levels of the contraceptive in their bodies.1 But levels were still high enough to prevent pregnancies, the researchers say.

In the same study, the researchers also found a few s that were associated, though only slightly, with lower levels of contraceptive hormones. At least one of these s controls how our bodies metabolize sex hormones, which can change how long it takes for the active ingredients in hormonal contraceptives to break down. That means a person’s genetic makeup could change how effective some options are for them.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

‘Perfect use’ vs ‘typical use’ in

When most s report their effectiveness, the number you see assumes what is called “perfect use.” That means it only considers users who follow the instructions perfectly and consistently — like always taking your daily oral contraceptive pill at the same time and never missing a dose.

But we all know people are imperfect. We snooze our alarm or forget to bring it with us when we go out. We slip up when applying a spermicidal gel. It’s tough to meet the ideal consistently, no matter how careful you are.

Different types of have different outcomes after less-than-perfect use. For some methods, a slip-up might knock the effectiveness rating down a few percentage points, increasing the risk of pregnancy just a little. But for others, mistakes can be catastrophic, as if you hadn’t attempted to use the contraceptive at all (think: a torn condom).

Luckily, s often report their effectiveness with “typical use” in addition to “perfect use,” though we might have to search harder to find this information. Typical use ratings are based on real-life data, averaging across real people who might forget to take a pill from time to time. Effectiveness of with typical use is an important piece of understanding what you should expect your to do for you.

Which s are highly effective?

Highly effective is available. Knowing which method to choose can be difficult and time-consuming. Here are some of the most commonly used forms of and how effective they really are:

Condoms

The classic condom, one of the most commonly used methods of , is said to be 98% effective with perfect use. But condoms aren’t always reliable: In a 2017 study, 7% of women between the ages of 15 and 44 who had used a male condom in the past four weeks said that the condom slipped or fell off during intercourse.2 The effectiveness of condoms slips to 85% for typical use.

Similarly, internal condoms, also called female condoms, drop from 98% effective with perfect use to 79% effective with typical use. They have a risk of spilling their contents during removal, and like male condoms, can slip or break during use.

That said, condoms are the only method that also help to prevent sexually transmitted infections. For that reason, using a condom is a good idea even if you’re also using another method of .

Spermicide and other gels

Other options involve gels that users put in their vaginas shortly before intercourse. These options, sometimes called spermicide gels, typically act by halting sperm or destroying them so they can’t reach the egg. Unlike condoms that might visibly break during use, gels have no sign of not working if something goes wrong. That means you won’t know to seek emergency contraception should something go wrong.

Even with perfect use, spermicides are only about 82% effective in preventing pregnancy. With typical use, they’re 72% effective. That means 28 out of 100 — or 7 in every 25 — women relying on spermicides for will get pregnant every year.

Other vaginal gels, like those with the active ingredients lactic acid, citric acid, and potassium bitartrate (like Phexxi, formerly known as Amphora and ACIDFORM), work by lowering the pH in the to stop sperm from moving. They’re 93% effective with perfect use and only 86% effective with typical use.3

The withdrawal, or pull-out method

One of the most straightforward ways to reduce the odds of pregnancy is for the sperm-bearing partner to pull out of the before ejaculating. But this is not a trustworthy means of , especially when used alone.

Researchers estimate the so-called , or “pulling out,” is about 82% effective at preventing pregnancy with typical use,4 meaning 18 out of 100 — or almost 1 in 5 — couples using this method will get pregnant each year. Effectiveness with perfect use for the isn’t always reported since it is so difficult to achieve (it is estimated to be around 96%,5 but again, this is difficult to scientifically measure). It is also worth noting that even pre-ejaculate can contain sperm.6

The morning-after pill

People can use emergency contraception like levonorgestrel, the morning-after pill, after unprotected sex or a failure. It is reportedly 95% effective at preventing pregnancy if taken within 24 hours, and 61% effective when taken between 48 and 72 hours after unprotected sex or a failure. Doctors recommend using emergency contraception as a single-use option and not on a regular basis.

A study from 2015 found that the morning-after pill is significantly less effective in people with higher body weight.7 Across 1,700 women, less than 2% who weighed under 165 lbs got pregnant (over 98% effectiveness), but those over 165 lbs saw a 6% pregnancy rate (94% effectiveness). That means people with a higher BMI may want to seek alternative forms of emergency contraception, like copper IUDs.

Is adyn right for you? Take the quiz.

Most effective: The pill, the patch, and more

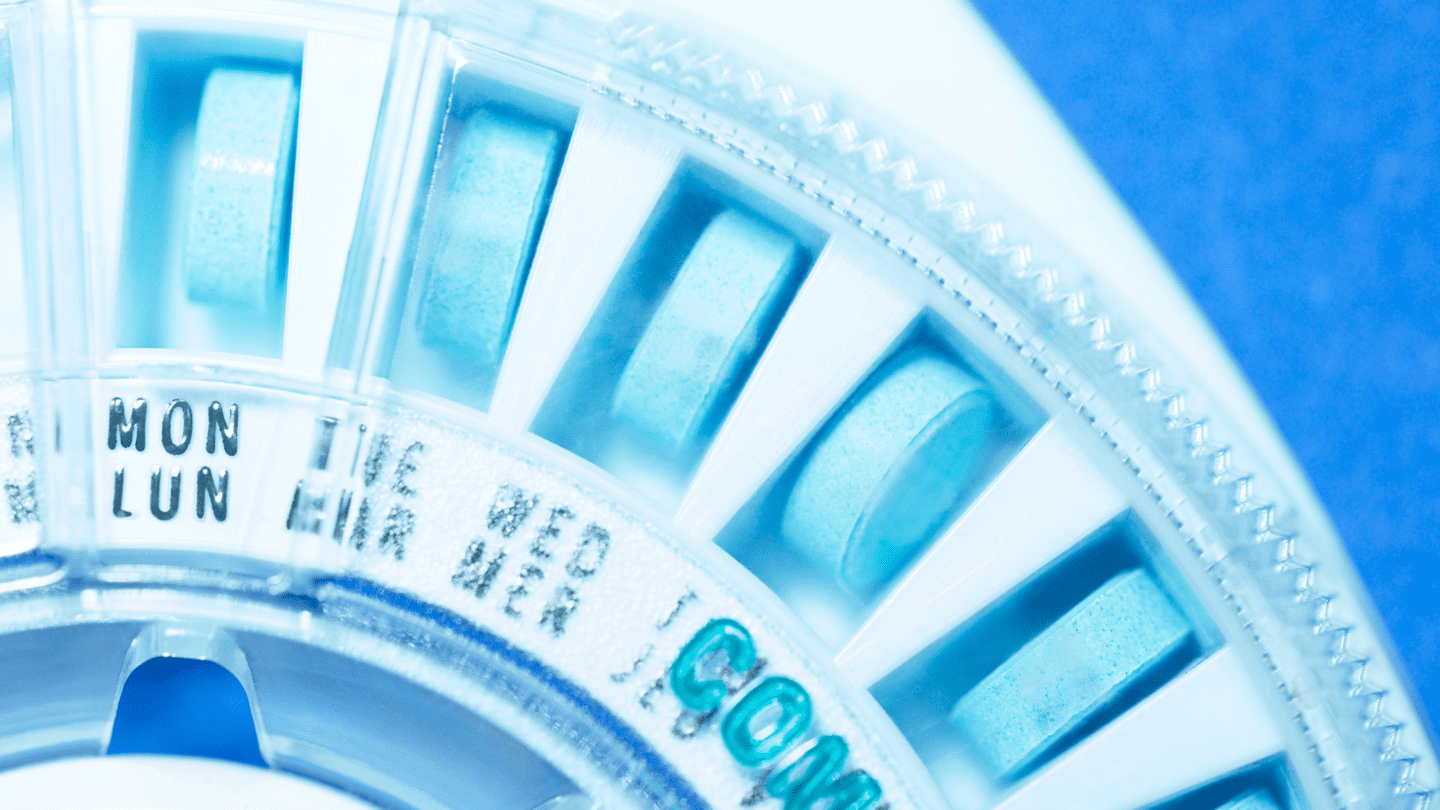

You can also have delivered by shots, patches, vaginal rings and pills. All of these are 99% effective when used correctly, but a bit less effective in typical use. The shot is 94 effective with typical use, and the patch, ring and pill are all 91% effective in typical use.

The birth control shot contains , a synthetic version of the sex , and works to prevent ovulation. To meet the definition of perfect use, you’ll need to get the shot every three months.

Birth control patches are small, sticky patches that you put on your stomach, back, or butt that release the hormones and . You replace the patch once a week for three weeks, and then take a week off before starting the cycle again.

You place birth control rings in your , where they release and . How you use them depends on the type of ring you select. Some must be replaced every month, while others last for a year and are inserted for three weeks, then removed for a week.

Birth control pills also release sex hormones; some contain both and , while others have just (the ). The amount of hormones can vary by pill, and gives you options depending on what’s right for you. You take birth control pills once a day, and some allow for the same kind of “three weeks on, one week off” cycle as the patch or ring.

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implanted contraceptive devices are both more than 99% effective, no matter what. IUDs are inserted into your by doctors, and last 3 to 12 years, depending on which kind you choose. Some IUDs work by releasing hormones into your body, while others use copper, which changes the lining of the and alters how sperm swim. Contraceptive implants are inserted into your arm and release sex hormones to prevent pregnancies. We consider both to be among the most highly effective methods of you can choose from.

Choosing highly effective

When you’re deciding which is right for you, it’s important to find one that’s both highly effective at preventing pregnancies and will have the minimum possible adverse side effects for you. For instance, you might want to avoid if you have a history of blood clots or heart disease, and smoke over the age of 35. Conversely, you might be taking a hormonal birth control for a reason other than to prevent pregnancy, like to treat , menstrual bleeding disorder, or migraines (without aura). It’s important to be sure you’re getting the effects you want from your , and not those you don’t.

If you do choose a option with less effectiveness (under 99%), you may want to consider combining multiple types of . For example, you might use condoms in addition to an oral contraceptive, or combine multiple non-hormonal options, like using both a vaginal gel and the .

For a rough estimate of combination effectiveness, multiply the risk of pregnancy (1 minus the effectiveness as a decimal) for each method. For instance, to find the combined risk of internal condoms (79% effectiveness with typical use) plus pH-lowering gels (86% with typical use), you would multiply 0.21 x 0.14. The risk of pregnancy using both methods together is around 0.03, or 3% (which means 97% effectiveness). Note that this calculation is just to give you a general idea, and does not account for interaction effects that might occur between the methods. And never combine multiple hormonal contraceptives!

When it comes to your options, the stakes are high. A pregnancy is life-changing, and adverse side effects can be deadly. A few percentage points difference in effectiveness can completely change the course of your life.

Don’t settle for less — get the right for your body.

-

- Lazorwitz, A., Aquilante, C. L., Oreschak, K., Sheeder, J., Guiahi, M., & Teal, S. (2019). Influence of genetic variants on steady-state etonogestrel concentrations among contraceptive implant users. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 133(4), 783.

- Copen, C. E. (2017). Condom Use During Sexual Intercourse Among Women and Men Aged 15-44 in the United States: 2011-2015 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports, (105), 1-18.

- Thomas, M. A., Chappell, B. T., Maximos, B., Culwell, K. R., Dart, C., & Howard, B. (2020). A novel vaginal pH regulator: results from the phase 3 AMPOWER contraception clinical trial. Contraception: X, 2, 100031.

- Kost, K., Singh, S., Vaughan, B., Trussell, J., & Bankole, A. (2008). Estimates of contraceptive failure from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Contraception, 77(1), 10-21.

- Killick, S. R., Leary, C., Trussell, J., & Guthrie, K. A. (2011). Sperm content of pre-ejaculatory fluid. Human Fertility, 14(1), 48-52.

- Jones, R. K., Lindberg, L. D., & Higgins, J. A. (2014). Pull and pray or extra protection? Contraceptive strategies involving withdrawal among US adult women. Contraception, 90(4), 416-421.

- Kapp, N., Abitbol, J. L., Mathé, H., Scherrer, B., Guillard, H., Gainer, E., & Ulmann, A. (2015). Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception, 91(2), 97-104.