When the Supreme Court overturned its landmark 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade this June, removing the federally-guaranteed right to an abortion, it put the topic at the forefront of so many of our thoughts and conversations.

People are wondering what their legal rights are and how their healthcare will be affected. And people are more curious — and opinionated — than ever about biology, ethics, and what’s really going on the first few days after conception. They’re good questions to ask: Whatever your beliefs on abortion, we all have a right to know what’s going on inside our bodies.

One question that we’ve been hearing more often is: Is ever considered an abortion? This is important to consider, since the answer affects whether contraceptives could be banned in places where abortions are illegal, and, for some people, could affect which contraceptives they’ll choose.

The short answer is: Birth control is not an abortion. An abortion is defined as ending a pregnancy, and pregnancy begins when an embryo is implanted in the .

Birth control prevents eggs from being fertilized, and it doesn’t affect embryos that have already implanted. Even contraceptive options like the morning-after pill don’t terminate a pregnancy, they can only prevent one from occurring.

Here’s a run-down of how different contraceptive options work to prevent pregnancy — and why each one is not an abortion.

How contraceptives typically work

Most contraceptives work by preventing fertilization from happening. The goal is for sperm to never meet an egg. Contraceptives achieve this by taking the egg, sperm, or both, out of the equation.

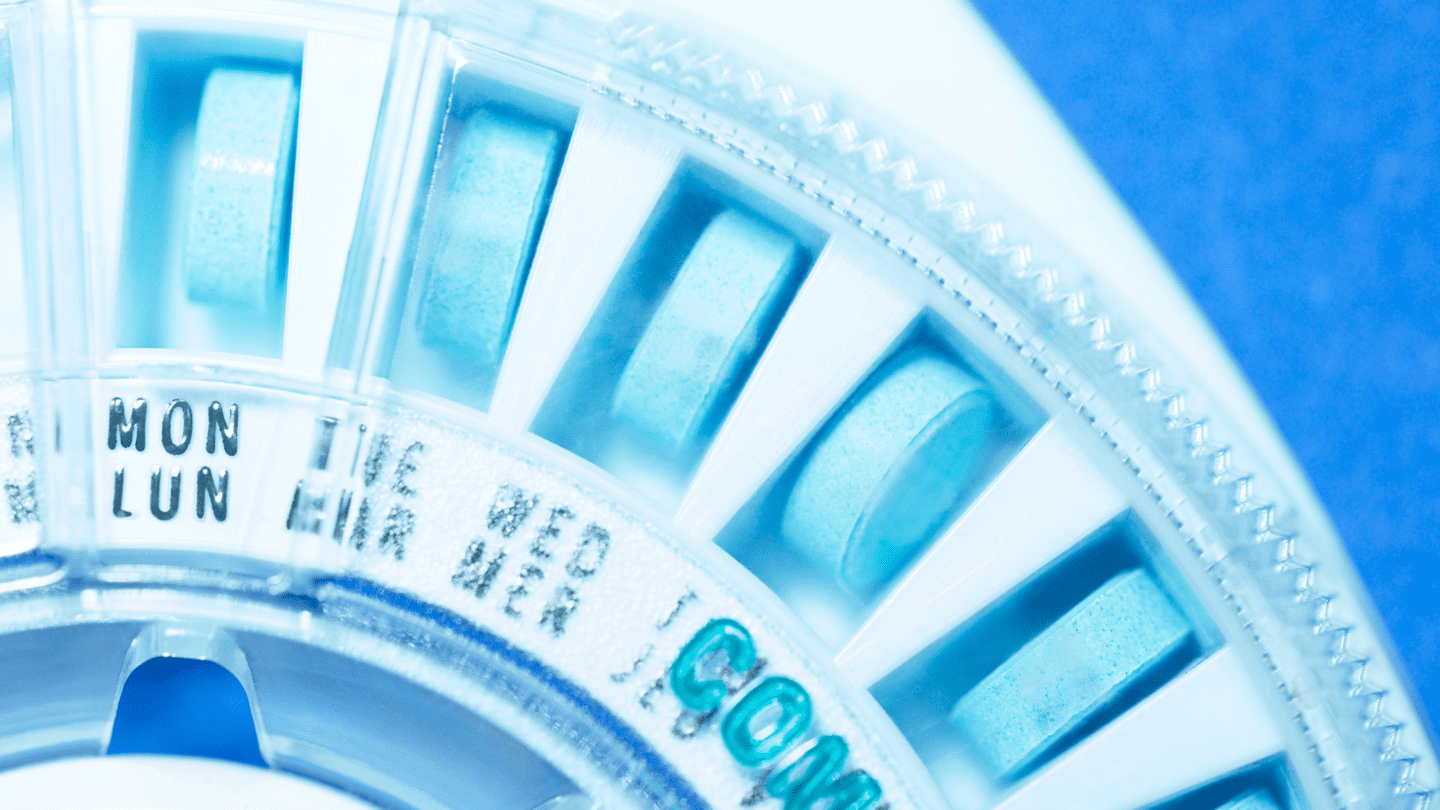

Physical methods of , like condoms or diaphragms, put a physical barrier between the sperm and eggs. Hormonal methods, and even the morning-after pill, predominantly work by preventing ovulation.1 The and/or contained in the pill, shot, implant, IUD, and other hormonal contraceptives signal to the body that the don’t need to release an egg. In this case, it doesn’t matter what the sperm are up to — there’s no egg in sight to fertilize. No egg, no fertilization, no pregnancy — and no abortion at any step of the way.

One of the biggest misconceptions is that the morning-after pill, or Plan B, is an abortion pill. It’s not. The morning-after pill is just a big dose of — which can prevent ovulation and block fertilization. Copper IUDs can be used as emergency contraception, too, and work differently: The copper changes the chemistry of your , for instance, preventing sperm from swimming.

Is adyn right for you? Take the quiz.

If you’re wondering: Abortion pills containing mifepristone work by blocking in the body. This causes the lining of the to break down, preventing the pregnancy from continuing.2

But… there’s a second (and third) line of defense

A number of hormonal contraceptives have secondary and tertiary mechanisms of action — that’s just a fancy way of saying that if the first line of defense (preventing ovulation) fails, there are a few other fail-safes in place. For example, , one of the hormones in hormonal contraceptives, also thickens cervical mucus, which makes it more difficult for sperm to get to an egg.

And if that doesn’t work, hormonal birth controls can also prevent a fertilized egg from implanting in the womb.1 Again, even if sperm were to fertilize an egg, you’re not actually pregnant until an embryo implants. But people who believe life begins at conception — meaning the moment sperm fertilizes an egg, regardless of whether it has implanted — might want to avoid using methods of that allow any fertilization. So how often does allow conception, but prevent pregnancy?

This is where the evidence is, unfortunately, slim. General consensus is that fertilization while on is rare, but a few researchers claim that it’s more common than we think: In one review study, scientists found that just over 7 percent of IUD users showed signs that eggs had been fertilized but had not resulted in a successful pregnancy.3 But when they only included “good-quality” studies, the number dropped to about 4.5 percent.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

In another review study, this time looking at just Plan B, researchers reported that emergency contraceptives might work by preventing ovulation in as little as 15 percent of cases — meaning the other 85 percent of the time that Plan B works, it’s after fertilization.4

It should be noted that both of these two studies were published in The Linacre Quarterly, a bioethics journal and the official publication of the Catholic Medical Association.5 What’s more, the authors’ affiliations include the American Association of Pro-Life OBGYNs, and in both studies, the researchers acknowledge their work directly contradicts findings from other groups. This certainly doesn’t mean that the work isn’t rigorous, trustworthy, or factual — it’s just important to be aware that some amount (and possibly a large amount) of religious-based ethics may be motivating those two studies.

Besides what’s in these two studies, we couldn’t find any other research to support the claim that eggs are fertilized while on . The vast majority of research supports the idea that prevents ovulation, with the exception of the , which works primarily by thickening cervical mucus to prevent passage of sperm.

Currently, FDA labels for both Plan B and Ella (both emergency contraceptives), say that they may block fertilized eggs from implanting in the . But the FDA announced in January 2023 that this will be changing in an upcoming label update. This makes sense because, as a blog from Harvard Law points out, “nobody can identify a legitimate scientific basis for those statements [that emergency contraceptives block implantation]. More to the point, scientific studies undermine them.”6 As far as we can tell, the copper IUD is the most likely emergency contraceptive option to work by preventing a fertilized egg from implanting, since it doesn’t block ovulation.7 Still, this hasn’t been proven8 – copper IUDs mainly work by killing sperm and preventing fertilization, too.9

As usual, all signs point to one thing: More research is needed. Any research is needed. Women, and all people with uteruses, are dramatically under-studied — and what actually happens in the body after taking contraceptives is no exception.

What counts as a pregnancy, anyway?

Again, most forms of work, first and foremost, by preventing sperm from meeting egg. That means you have nothing to worry about, since it prevents fertilization and therefore prevents pregnancy. If, against the odds, an egg is somehow fertilized and a viable embryo is created, many forms of also may prevent the embryo from implanting, therefore preventing a pregnancy.

Pregnancy fast facts:

- Conception is the moment of fertilization — when a sperm meets an egg, and creates a single-celled . This happens in the fallopian tubes.

- The stage lasts about 30 hours, until the cell starts dividing.10

- An embryo doesn’t implant into the womb until about days 6 to 12 after conception.11 At that point, pregnancy begins.

- Clinical providers measure pregnancy from the first day of the last period because it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when conception has occurred. With a 28-day cycle, ovulation takes place around day 14, meaning your embryo’s actual age is at least 2 weeks younger than your “pregnancy.” In other words, if you’re “6 weeks pregnant,” your embryo is a maximum of 4 weeks old, and probably has only been implanted for 3 weeks.

- This is the same reason why a full term is considered 40 weeks long, but a normal pregnancy can range between 38 and 42 weeks.

- Most people become aware of a pregnancy 3-7 weeks after conceptive sex (or, when they’re 5-9 weeks pregnant).12

- An ultrasound might detect a heartbeat, visually, around six weeks.13

- The embryo becomes a fetus at 8 weeks.

- You can tell a baby’s sex with an ultrasound around 14 weeks.14 A blood test can tell as early as seven weeks.15

Keep in mind that viable embryos are created all around the world for research and in IVF centers. Even under the best circumstances, a viable embryo doesn’t mean successful pregnancy. For instance, the Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority estimated that from 1991 to 2019, 1.3 million IVF cycles in the U.K. — each with multiple embryos created in vitro — resulted in only 390,000 babies born.16

Additionally, without , it’s estimated that as little as 40 percent of fertilized eggs actually end up as a baby.17

Again, no options work after implantation, aka after pregnancy has begun. That would be an abortion.

Can kill a fetus?

No forms of can terminate a pregnancy. In fact, if you take when you’re already pregnant, research suggests there’s not even an increased risk of birth defects.18 The main contraception-related risk to a fetus is the IUD: If you were to get pregnant with an IUD in place, you’d have a higher chance of miscarriage due to having a device physically in your – there are risks to the fetus both from leaving it in place, as well as from removing it.19

Some people might want to avoid using that could allow an egg to be fertilized, creating an embryo, even if implantation and pregnancy never occurs — those people should choose hormonal IUDs and use multiple methods (like condoms, used perfectly, or pulling out in addition to a ) to decrease the odds as much as possible. Of course, the only method that is nearly 100 percent effective at preventing pregnancy is vasectomy or tubal ligation sterilization (and even they have a rare failure).20

In the end, though, rest assured that using — of any kind — is never an abortion.

-

- InformedHealth.org. “Contraception: Hormonal contraceptives.” Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. (Updated 2017 Jun 29): Accessed 2022 Oct 12

- Planned Parenthood. “The Facts on Mifepristone.” PlannedParenthood.org (2019 Oct): Accessed 2022 Oct 18.

- Buskmiller, Cara, et al. “Systematic Review of Postfertilization Effects and Potential for Embryo Formation and Loss during the Use of Intrauterine Devices.” The Linacre Quarterly 87.1 (2020): 60-77.

- Peck, Rebecca, et al. “Does levonorgestrel emergency contraceptive have a post-fertilization effect? A review of its mechanism of action.” The Linacre Quarterly 83.1 (2016): 35-51.

- Description of The Linacre Quarterly: https://journals.sagepub.com/home/LQR

- Lipper, Gregory M. “Zubik v. Burwell, Part 3: Birth Control Is Not Abortion.” Bill of Health blog of the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School. (2016 Mar 19): Accessed 2022 Oct 12.

- Michie, L., and S. T. Cameron. “Emergency contraception and impact on abortion rates.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 63 (2020): 111-119.

- ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. “Intrauterine devices and intrauterine systems.” Human Reproduction Update 14.3 (2008): 197-208.

- Planned Parenthood. “Copper (Paragard) IUD for Emergency Contraception.” PlannedParenthood.org (N.D.): Accessed 2023 Jan 25.

- National Library of Medicine. “Cell Division.” Medline Plus (2021 Sep 07): Accessed 2023 Jan 25.

- Planned Parenthood. “Pregnancy Testing.” PlannedParenthood.org (N.D.): Accessed 2023 Jan 25.

- Grant, Azure, and Benjamin Smarr. “Feasibility of continuous distal body temperature for passive, early pregnancy detection.” PLOS Digital Health 1.5 (2022): e0000034.

- McDonald, Jessica. “When Are Heartbeats Audible During Pregnancy?” Factcheck.org (2019 Jul 26): Accessed 2022 Oct 12.

- Kearin, Manette, Karen Pollard, and Ian Garbett. “Accuracy of sonographic fetal gender determination: predictions made by sonographers during routine obstetric ultrasound scans.” Australasian Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 17.3 (2014): 125-130.

- Ormstad, S. S. et al. “Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for foetal sex determination,” Norwegian Institute of Public Health (2016 Dec).

- Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority. “Fertility treatment 2019: trends and figures.” HFEA.gov.uk (2021 May).

- Jarvis, Gavin E. “Early embryo mortality in natural human reproduction: What the data say.” F1000Research 5 (2016).

- Charlton, Brittany M., et al. “Maternal use of oral contraceptives and risk of birth defects in Denmark: prospective, nationwide cohort study.” BMJ 352 (2016).

- FDA. “Highlights of Prescribing Information: Paragard (intrauterine copper contraceptive).” (2019 Sep): Accessed 2022 Oct 12.

- Date, Shilpa Vishwas, et al. “Female sterilization failure: Review over a decade and its clinicopathological correlation.” International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research 4.2 (2014): 81.