Burning, itching, weird smells, and abnormal discharge are your ’s way of telling you something might be off down there. It’s important to pay attention to these changes, as they can be a sign that your body is experiencing hormonal changes, feeling irritated, or fighting off an infection.

In many cases, abnormal vaginal symptoms can be an indicator that you have bacterial vaginosis (BV). BV is an extremely common condition that affects 30% of women assigned female at birth in the U.S. between the ages of 14 and 49.1 Chances are, you probably know someone who has had BV — or maybe you’ve had it yourself.

So how does someone get BV? There isn’t just one answer, since BV can happen for multiple reasons. One factor in bacterial vaginosis could be your , which some studies show can affect your odds of getting it, or having it come back. Research on this topic is still limited, so we need to learn more, but studies show that some methods increase BV risk while others decrease it.1,9-11

We’re here to answer all your burning questions about BV and . Read on to learn about the causes of BV, what to do if you have it, and how common contraceptives, like IUDs and condoms, can play a role.

What is bacterial vaginosis?

Bacterial vaginosis is a common condition that typically causes abnormal vaginal discharge, bad smells, and uncomfortable sensations around the , like itching or burning. As the name suggests, BV happens when your body has a bacterial imbalance. Similar to how a yeast infection is due to an overgrowth of naturally-occurring fungus in the body, BV happens when certain species of bacteria in the outnumber others.2-3

Bacterial vaginosis is the most common cause of abnormal discharge among people of reproductive age, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).3 If you have BV, odd discharge will likely be one of the first symptoms you’ll notice. While it’s totally normal to have discharge at different points in your menstrual cycle, pay attention to any that seems like it’s out of the ordinary for your body, in color, quantity, or texture. (BV discharge typically looks off-white or light gray.)

You may also notice a musty or fishy smell coming from down there. And itching or burning — sometimes while peeing — is also a common symptom that people experience with BV. However, you can have bacterial vaginosis with no symptoms at all, and may not know until your doctor does a formal test.

BV is more common in people who are sexually active.4 You can get it from a sexual partner, but only if your partner has a , too. But there are so many ways for BV to happen that knowing where it came from isn’t usually so simple. It’s just that common.

There are so many ways for BV to happen that knowing where it came from isn’t usually so simple.

If you do think you have BV it’s important to seek treatment, because it can cause complications when left untreated. For example, having BV makes you more susceptible to STIs and more likely to transmit them.4 And if you have BV while you’re pregnant, it may cause you to give birth early, increasing the chances that your baby may be underweight and experience other complications.5

What causes bacterial vaginosis?

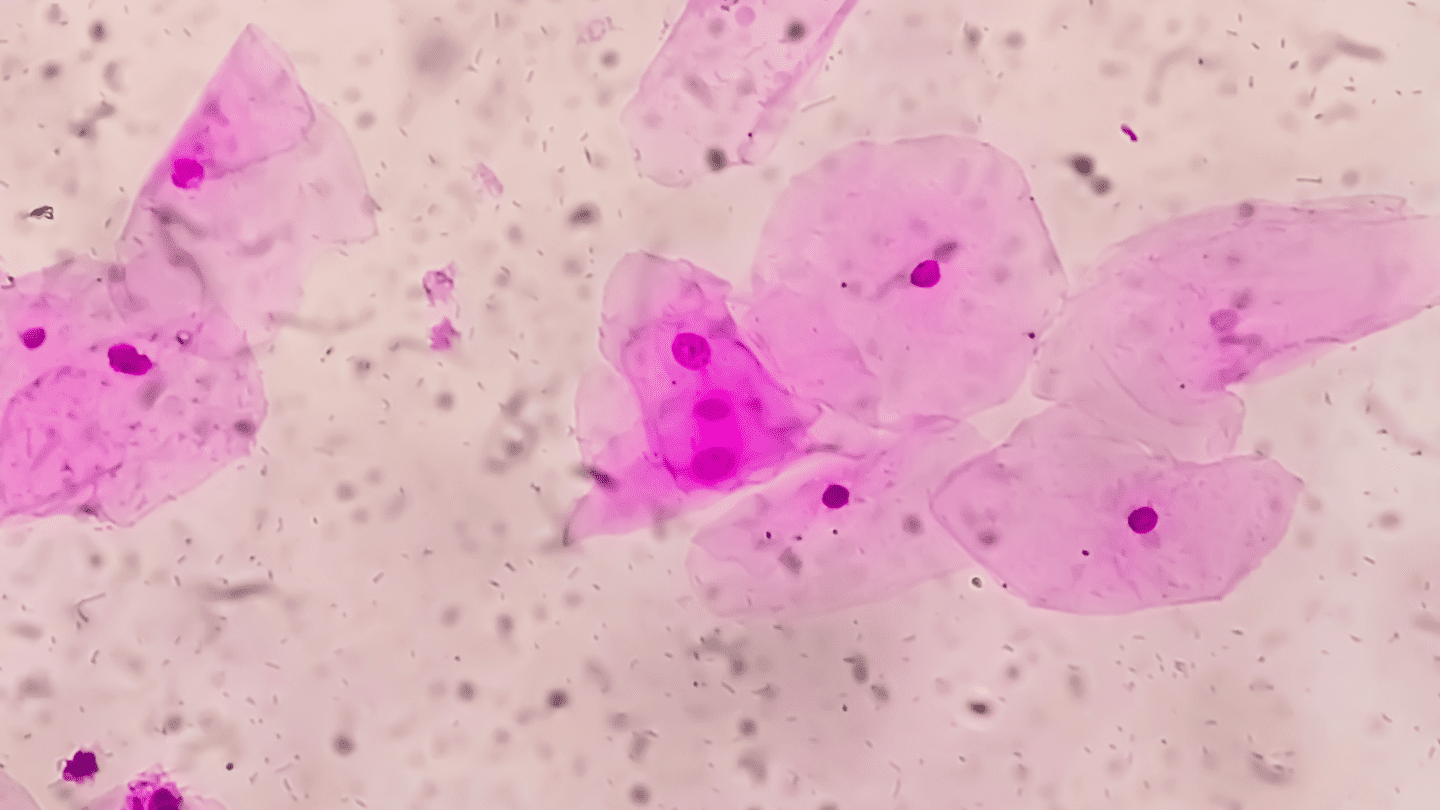

To understand how BV happens, we need to take a look at one of the most important – yet invisible – parts of your reproductive system: the vaginal microbiome. (You’ll also hear it called vaginal flora.)

Your is home to billions of good bacteria that keep you healthy.6 Several different species work together to create a balanced ecosystem that changes and adapts to hormonal fluctuations in your body. But you can largely thank the bacteria Lactobacillus, since it’s the most populous strain in the vaginal microbiome.

When Lactobacillus colonies are outnumbered by other types of bacteria, it can cause an imbalance in the microbiome that can lead to inflammation and make the environment more friendly to other bad bacteria.This is what causes BV and the pesky symptoms that come with it.6 So how do you get an imbalance?

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

The makeup of your microbiome can be altered by things we do to our bodies. Douching, for example, can deplete Lactobacillus colonies in the vaginal microbiome and raising your risk of BV.1 Not using condoms or wearing them inconsistently, and having multiple sexual partners can also alter your vaginal microbiome and make you more susceptible to developing the condition.4

But other times, BV happens due to internal changes. Hormonal shifts, like those that happen during , can put people at higher risk for BV – especially if they are sexually active or receiving treatments.7 And people with hormonal conditions like (PCOS) tend to have higher rates of BV than those who don’t, likely due to the hormonal fluctuations those conditions cause.8

Can cause BV?

Because BV is such a common condition, many people who have it also happen to be on birth control. Very little scientific research has examined how specific methods affect BV, and the current scientific evidence is inconclusive as to whether can cause BV or make it worse.

So far, research on combined oral contraceptives (the pill) shows they either decrease or have no impact on a person’s risk of BV. Some studies have found that the vaginal bacterial composition of women on the pill didn’t significantly change over time, while other studies have shown that the pill appears to promote healthy vaginal conditions for Lactobacillus bacteria to thrive.9,1 Additionally, using condoms regularly10 or taking progestin-only pills (aka the mini-pill) seems to provide a protective effect against BV.9

Is adyn right for you? Take the quiz.

IUDs and bacterial vaginosis

With IUDs, the results are a bit different. One study from 2021 compared bacterial vaginosis rates in women on different types of , and found that those with copper IUDs had the highest rates of BV (by about 25%).11 Cases of bacterial vaginosis were particularly high during the first six months after IUD insertion.

Another study compared bacterial vaginosis rates in women with both hormonal and copper IUDs to women on the pill, ring, or patch.11 The researchers found that those with IUDs who experienced irregular bleeding, a common side effect of some methods, seemed to be the most susceptible to bacterial vaginosis. While the link isn’t fully understood, some researchers think the environmental changes caused by irregular bleeding can also lead to BV.1,11

So, does BV go away after IUD removal? In the case of the copper IUD, the number of BV cases typically decline to pre-insertion levels one year after the device is taken out.11 For the hormonal IUD, some evidence shows the risk of BV may similarly go back to normal starting within a year after taking it out.12 So, taking an IUD out might help.

The link between IUDs, irregular bleeding, and bacterial vaginosis still isn’t fully understood. It may be that the presence of the IUD itself, not the hormones it releases can lead to BV. Additionally, some studies don’t show an increase in BV risk from IUDs at all.11 It’s another example of the medical research gap, and we need more research to know more about the topic. In general, it’s possible your could make you more susceptible to BV, though there are other factors that could be at play, too. If you have BV, the most important thing is to seek treatment for your symptoms as soon as you can.

What to do if you get BV while on

The good news about BV is that it is generally easy to treat and doesn’t often cause serious complications when addressed promptly. If you have symptoms, be sure to see a doctor, especially if you are pregnant. They will likely prescribe an antibiotic gel or pill to help clear up the symptoms.3

Bacterial vaginosis also often comes back within a few months after clearing up.14 So if you start having symptoms again, you may need another round of antibiotics to get things back on track.

There are some things you can do to make your odds of getting BV better (like not douching regularly). Things like changes in diet can also make a difference for the vaginal microbiome. One study found that diets high in sugars, red meats, and refined carbohydrates correlated with a higher risk of BV – and that diets that were mostly plant-based seemed to be associated with lower risk.15

If you just started a new method and are experiencing more frequent or worsened cases of BV, talk to your doctor about it. There’s a possibility, especially if you have irregular bleeding after an IUD insertion, that your may be affecting your microbiome in a negative way.

Whether or not your is to blame, don’t worry about trying out a different method. There are so many options to choose from to find one that’s right for your body.

Looking for a that suits your unique biology? Try The Birth Control Test.

-

- Bakus, C., Budge, K. L., Feigenblum, N., Figueroa, M., & Francis, A. P. (2022) The impact of contraceptives on the vaginal microbiome in the non-pregnant state.” Frontiers in Microbiomes. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiomes/articles/10.3389/frmbi.2022.1055472/full

- Yeast infection. Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2019, December 2). https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/candidiasis-yeast-infection

- Bacterial Vaginosis. World Health Organization. (2016). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/bacterial-vaginosis

- About Bacterial Vaginosis (BV) CDC. (2023). https://www.cdc.gov/bacterial-vaginosis/about/index.html

- Does vaginitis affect a pregnant woman & her infant? NIH. (2022 Feb 11). https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/vaginitis/conditioninfo/pregnancy

- Chen, X., Lu, Y., Chen, T., Li, R. (2021). The Female Vaginal Microbiome in Health and Bacterial Vaginosis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-and-infection-microbiology/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2021.631972/full

- Van Gerwen, O.T., Smith, S.E., Muzny, C.A. (2023). Bacterial Vaginosis in Postmenopausal Women. Current Infectious Disease Reports 25 (2023): 7-15. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11908-022-00794-1

- Chudzicka-Strugała, I., Gołębiewska, I., Banaszewska, B., et. al. (2024). Bacterial Vaginosis (BV) and Vaginal Microbiome Disorders in Women Suffering from Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Diagnostics 14(4) (2024): 404 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38396443/

- Vodstrcil, L.A., Hocking, J.S., Law, M., Walker, S., et. al. (2013). Hormonal Contraception Is Associated with a Reduced Risk of Bacterial Vaginosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3762860/

- Yotebieng, M., Turner, A. N., Hoke, T. H., Van Damme, K., Rasolofomanana, J. R., & Behets, F. (2009). Effect of consistent condom use on 6-month prevalence of bacterial vaginosis varies by baseline BV status. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH, 14(4), 480–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02235.x

- Madden, T., Grentzer, J.M., Secura, G.M., Allsworth, J.E., Peipert, J.F. (2012) Risk of Bacterial Vaginosis in Users of the Intrauterine Device: A Longitudinal Study. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 39(3) (2012): 217-222 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3285477/

- Donders, G. G. G., Bellen, G., Ruban, K., & Van Bulck, B. (2018). Short- and long-term influence of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena®) on vaginal microbiota and Candida. Journal of medical microbiology, 67(3), 308–313. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.000657

- Peebles, K., Kiweewa, F.M., Palanee-Phillips, T., Chappell, C., et. al. (2021). Elevated Risk of Bacterial Vaginosis Among Users of the Copper Intrauterine Device: A Prospective Longitudinal Cohort Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 73(3) 513-520. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8326546/

- Bacterial vaginosis. NHS. (2022). https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/bacterial-vaginosis/

- Noormohammadi, M., Eslamian, G., Kazemi, N.S., Rashidkhani, B. (2022) Association between dietary patterns and bacterial vaginosis: a case-control study.” Scientific Reports. 12. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-16505-8