There is a question I still mull over when I think about who exercises control over the birth control pills millions of people take. When it comes to reproductive rights and justice, “Whose choice is it?”.

The unethical nature of the history of might be unsurprising to many of us who had some notion of the unethical experimental trials conducted on poor Puerto Rican women in the 1950s. The women were neither informed about the nature of the study nor the risks associated with the experimental drug.

But, did we know the same research team experimented first on institutionalized women diagnosed as severely mentally unwell in the United States? Are we aware that the Puerto Rican trial was the second one conducted and a third clinical trial occurred in Port au Prince, Haiti?

The history of in this country is one that is bound up in the unethical treatment of vulnerable populations, anti-blackness, and colonialism. There is a question I still mull over when I think about who exercises control over the birth control pills millions of people take. When it comes to reproductive rights and justice, “Whose choice is it?”.

So much about reproductive medicine, especially , is about the physician’s preference and not the patient’s. Bodily autonomy has been a tenet of feminism for nearly two centuries. Yet, women and people with uteri cannot choose the birth control pills that are best for their bodies and health.

In this nation, physicians have a heavy reliance on pelvic exams that do not test patients for Factor V Leiden, to assess whether the patient has a high risk for getting blood clots prior to taking birth control pills.

By 2018, physicians performed nearly 60 million pelvic exams on women and people with uteri who did not necessarily need the exams performed. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists just reaffirmed its Committee on Gynecologic Practice opinion “that pelvic examinations be performed when indicated by medical history or symptoms.”

Millions of women patients and patients with uteri have undergone invasive pelvic exams as a condition for receiving — even when the procedures might not have been needed.

How can we transform a medical industrial complex that is supposed to center women’s health and bodies, while it relies on practices that still are reminiscent of reproductive medicine’s unethical past? How can we create a democratic culture in reproductive medicine? I think providing historical context for how we arrived at this moment regarding “the pill” is important.

As a historian and author who writes about the history of reproductive medicine, I am never shocked by the of medical exploitation on certain marginalized populations. The history of the clinical trials was so transparently unethical that I was gobsmacked to learn how vocal one of the researchers, Dr. Gregory Pincus, was about his eugenicist beliefs.

Pincus and his colleagues were allowed to conduct their work on the mentally ill and brown and black people because medical racism and ableism existed and gave space for these women’s exploitation to happen. The following exchange between an heiress and activist evidences my point.

Eighty-year old American heiress Katherine McCormick was the country’s most influential individual investor in developing the first birth control pill. McCormick expressed her frustration about Massachusetts’ clinical gridlock. She wanted an easier way to procure patients.

“How can we get a ‘cage’ of ovulating females to experiment with?” she wrote to fellow advocate and pioneer, Margaret Sanger.

Her letter to Sanger detailed a conversation she had with Dr. Gregory Pincus, one of the pioneers of “the pill.” In a letter written to fellow advocate and pioneer Margaret Sanger, McCormick detailed a conversation she had with Dr. Gregory Pincus, one of the pioneers of “the pill.”

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

More than likely afraid of McCormick’s possibly withdrawing her financial support, within one day, Dr. Pincus informed her he would use mentally ill patients at the Massachusetts State Insane Hospital. Although McCormick penned the letter in 1955, the Supreme Court legally sanctioned informed consent in 1914. Regardless, physicians and research scientists continued to exploit marginalized and vulnerable populations in clinical trials.

Despite informed consent serving as a protective measure for patients and research participants, Dr. Pincus, a research scientist, and his partner physician John Rock, both Harvard trained researchers, decided to use severely mentally ill patients for the trial.

In 1954, the research began one of the United States’ first experimental trials on twelve women. All of the patients were considered “psychotic” and could not give consent but according to the laws of the time, their family members could provide consent to Dr. Pincus and Dr. Rock.

As a research scientist, Dr. Pincus was not supposed to participate in human trials, so Dr. Rock “led” the trial. This acted as a smokescreen, as Dr. Pincus was equally involved in the experimental trials. Further, they described their research as “fertility based”, gave the women an early form of the birth control pill, and made a uterine incision.

The researchers did so to evaluate if the pill would affect the patients’ ovulation. Pincus published his findings and faced considerable backlash from his peers. They criticized the unethical nature of his experiments on women so impaired they could not determine if it was a procedure, or if they wanted a procedure performed. Dr. Pincus remained undeterred.

Ephraim McDowell, known as the “Father of The Ovariotomy,” experimented over a nearly ten-year period on primarily enslaved women.

Dr. Pincus and his colleagues, including Katherine McCormick, were not unlike the elite doctors, scientists, and researchers of the nineteenth century who also pioneered medical branches like gynecology and obstetrics on vulnerable patient populations like the enslaved. Men like Ephraim McDowell, known as the “Father of The Ovariotomy,” experimented over a nearly ten-year period on primarily enslaved women.

McDowell was the first recorded gynecological surgeon to remove an ovarian tumor via abdominal incision successfully in 1809. By the time he published his findings in 1817, he was ridiculed. His colleagues, especially those in Europe, were not impressed that he obtained success with his abdominal-based surgical repair because the majority of his patients were Black women, all of whom were enslaved but one.

One of the reigning beliefs doctors had about Black women was about pain. Allegedly, Black women did not experience physical pain from childbirth or surgery either at all or slightly when compared to white women. Ultimately, his critics questioned the veracity of McDowell’s claims about his patients’ outcomes precisely because they believed Black patients were hardier and immune to surgical pain.

In the 21st century, we are disgusted that any medical researcher would think to exploit a patient’s body and health to develop or design a procedure, pharmaceutical product, and tool with punishment. Yet, Drs. Pincus and Rock especially inherited a cultural practice dedicated to maintaining a status quo, where vulnerable patients were at the mercy of doctors who were charged to care for them medically.

It is not surprising to me — a historian and author who has written extensively about the history of reproductive medicine in the United States — that a medical researcher responding to the frustration of a rich funder would work at warp speed to provide what his primary investor wanted for the birth control pill experiment to continue sooner rather than later.

Not to mention the unethical nature of the experiments on severely mentally ill women, Dr. Pincus and his team had disastrous results. Dosages were too high, patients suffered bleeding, mood swings, and bodily pain. Dr. Pincus dismissed these women’s symptoms and blamed them as suffering from “psychogenic” pain.

It was more conceivable for Dr. Pincus to believe women, who lived in three separate countries, all imagined their symptoms rather than he made errors.

In essence, the pain his patients felt was imagined and all in their heads. Unfortunately, Pincus repeated these claims about his patients for the remainder of his career. Even the researcher’s medical failures were not his fault but became his patients’ failures. It was more conceivable for Dr. Pincus to believe women, who lived in three separate countries, all imagined their symptoms rather than he made errors.

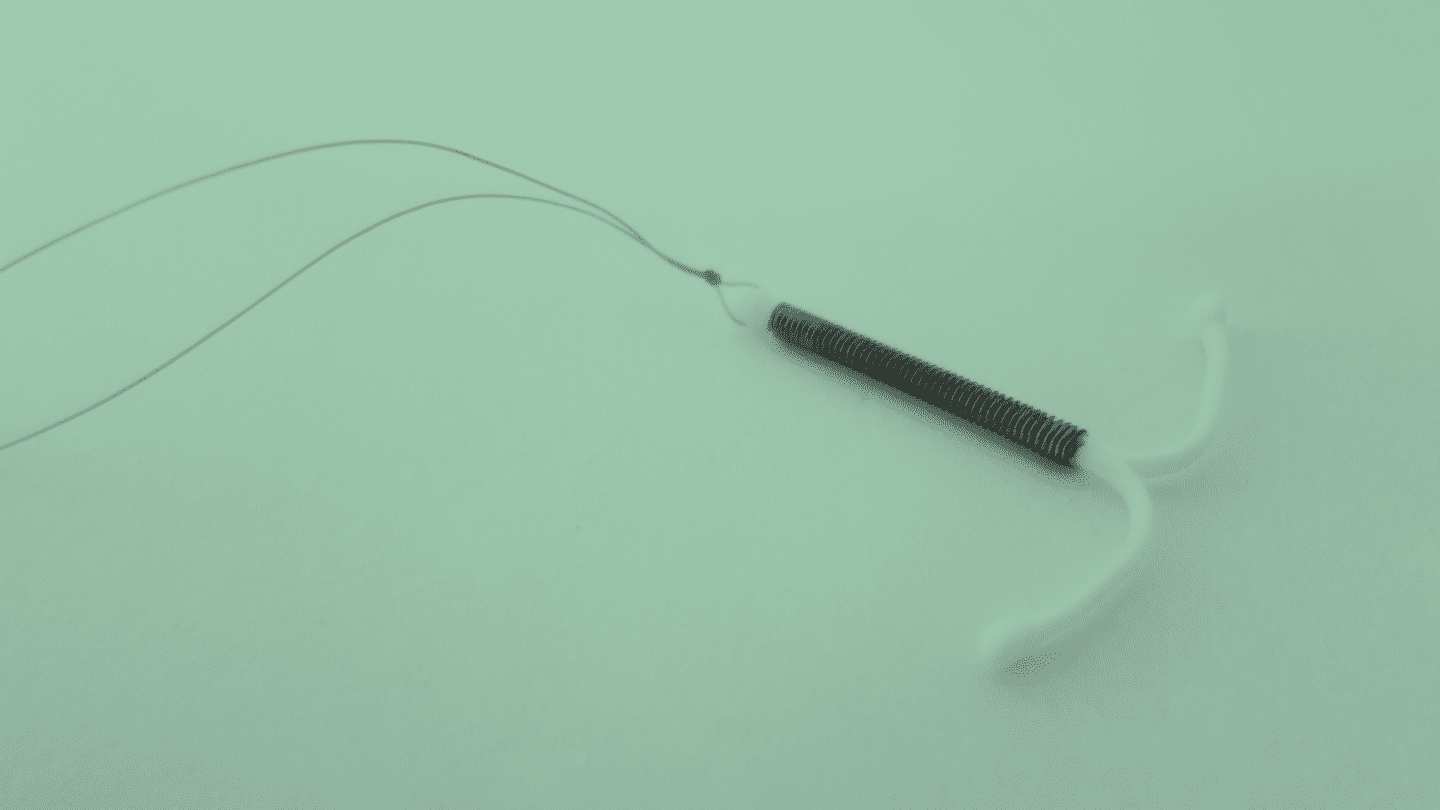

And so here we are in the 21st century still struggling with ethics, choice, and bodily autonomy when it comes to reproductive medicine. The birth control pill revolutionized women’s lives. Perhaps full bodily autonomy would be achieved with the launch of the pill in 1960?

But doctors rely more on invasive procedures like pelvic exams without testing whether patients have a genetic predisposition for blood clots, and far too many physicians prescribe birth control pills based on their preferences rather than what is healthier for the individual patient.

We must be steadfast in our work for for all to expand conversations about choice beyond abortion. also includes dismantling the structural impediments that are built into how patients are assessed for birth control pills and how they are prescribed.

Perhaps we are moving closer to the moment when we do not have to ask, “Whose choice?” about and our autonomy.

-

1. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/10/the-utility-of-and-indications-for-routine-pelvic-examination (accessed March 21, 2021).

3. Margaret Sanger Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College via http://www.shoppbs.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/pill/filmmore/ps_letters.html (accessed March 19, 2021)

4. See Cathy Moran Hajo. Birth Control on Main Street: Organizing Clinics in the United States, 1916-1939 (Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois Press, 2010).

5. See chapter 1 of Deirdre Cooper Owens’ Medical Bondage: Race, Gender and The Origins of American Gynecology. (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2017).