Can you prevent pregnancies just by paying attention to your cycle? The idea can sound enticing, especially if you’ve been burned by a bad experience with in the past. No hormones, IUD insertions, or intrusive condoms — just pay attention to what your body is telling you.

This approach to has popped up on the Instagram accounts of numerous influencers (#ad), and there are apps that claim to help you track your cycle and find out when it’s supposedly OK to have unprotected sex. You might see this kind of called the rhythm method or calendar method, or a few other kinds of “methods.”1 The general term is the fertility awareness method, or FAM.2

But FAM’s effectiveness is far below the gold standard of highly effective contraceptive options like s (IUDs). In fact, it’s the least effective form of .3 And FAM is tough to do right, with potentially big consequences for even small mistakes. Here’s what you need to know about FAM as .

What is FAM?

The fertility awareness method means paying attention to your cycle so that you don’t have unprotected sex at times when you might get pregnant. There are a few different ways to do this:

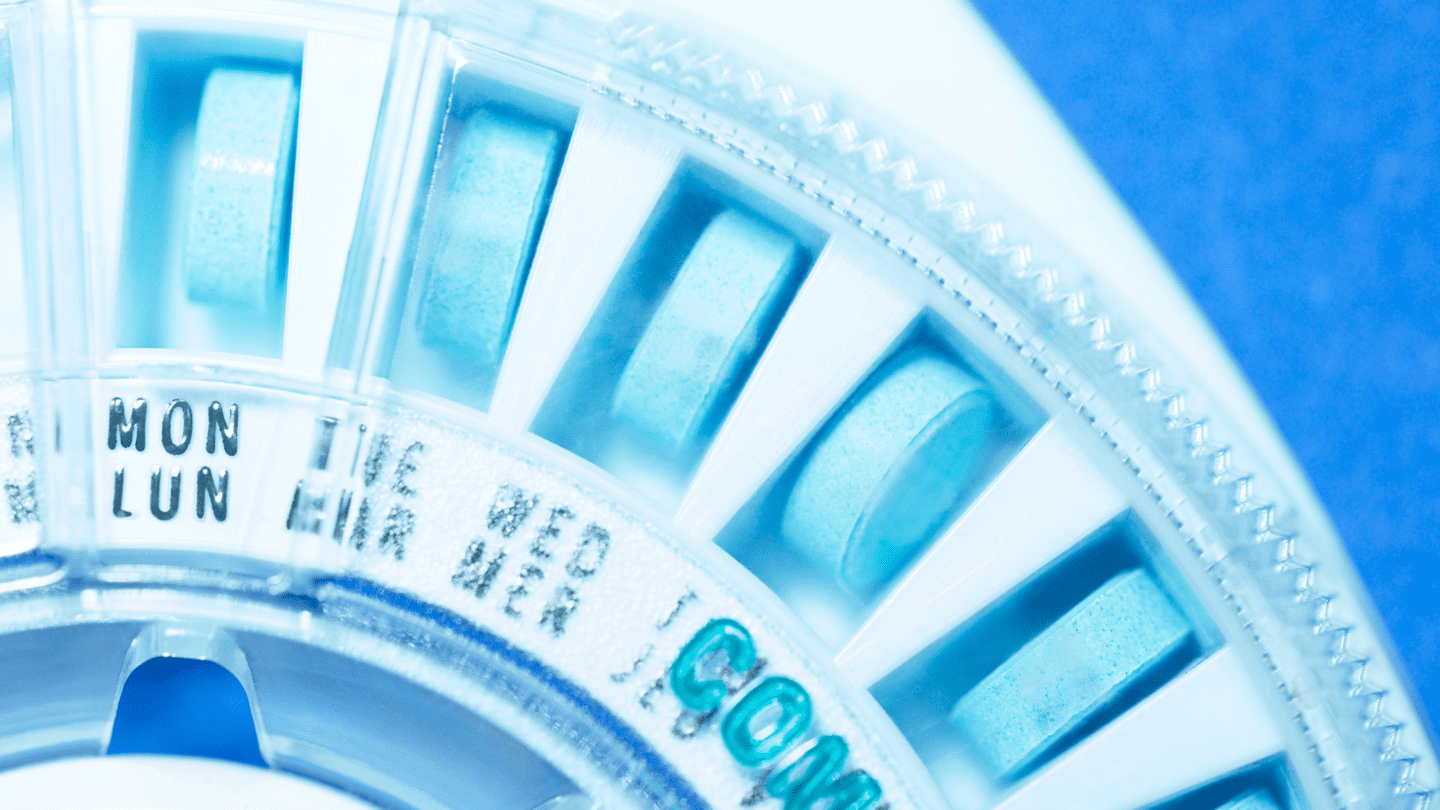

- The calendar or rhythm method: You ovulate between 12 and 16 days after your period ends. This method involves identifying which days after your period you might be fertile based on the shortest and longest cycles you’ve had in the past 6 months.5-6

- Basal body temperature: Your body temp is slightly higher when you’re ovulating. This method relies on taking your basal (AKA resting) temperature every morning, right when you wake up.5 It requires a specific type of basal thermometer that gives your temperature to two decimal places.7

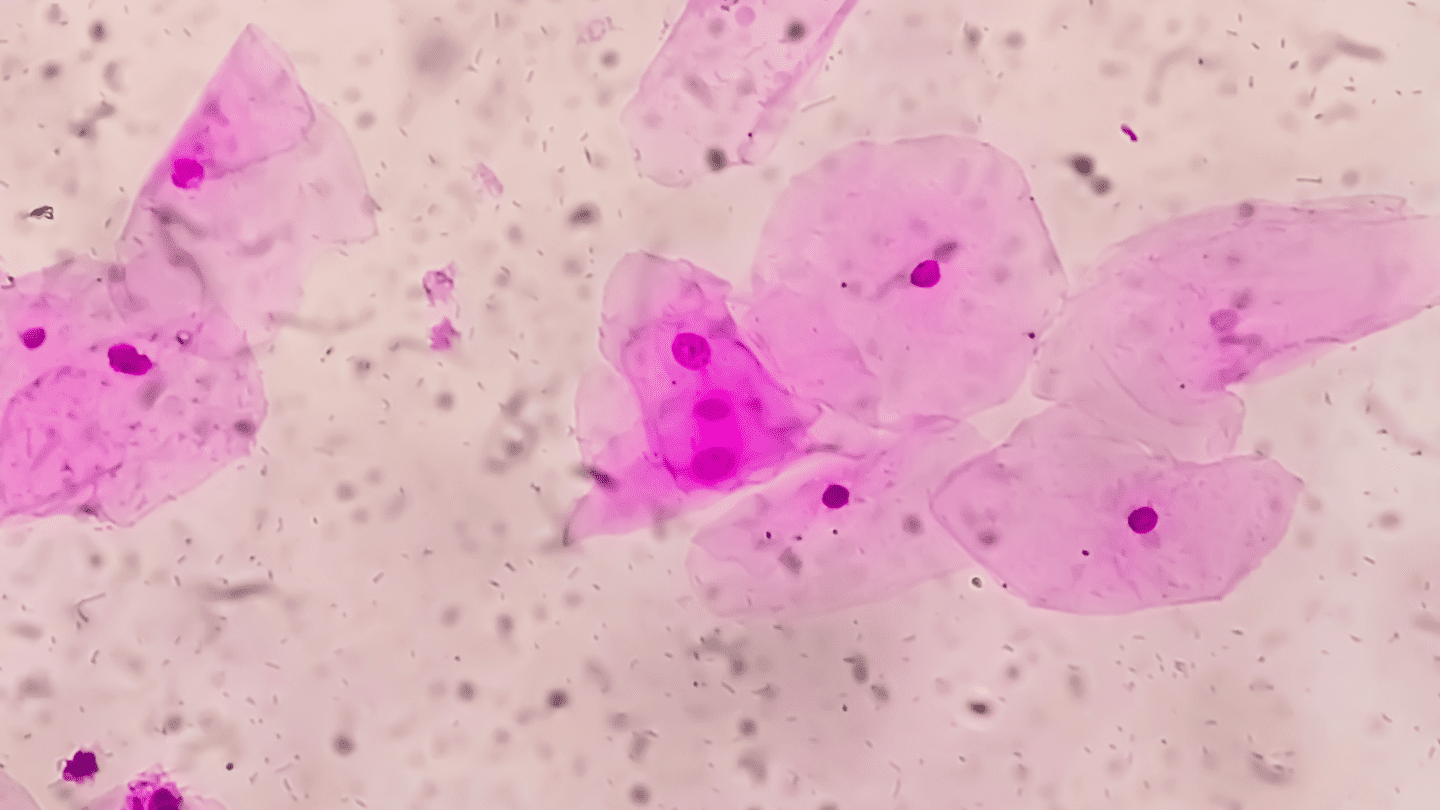

- The cervical mucus or Billings method: Cervical mucus gets stretchier, thinner, and slippery during ovulation. You can monitor changes in the mucus to see when you’re in danger of getting pregnant.5

- The Marquette method: This method relies primarily on using an electronic monitor that measures levels in the urine, sometimes in conjunction with measuring cervical mucus and basal temperature.8-9

You can also combine two or more of these methods to get multiple sources of information on your cycle. For example, the symptothermal method5 combines temperature measurements, cervical mucus monitoring, and other things to help gauge when you might be ovulating.

How does FAM as work?

The basic idea behind FAM is to not have sex when you’re ovulating. Ovulation is the period after an egg is released from your ,10 which happens around the midpoint of your cycle. Eggs typically live for less than 24 hours, and sperm can live inside the body for up to five days.11

So, if you avoid having sex for five days before ovulation and a day afterward (or use another method like a condom during that time), you should be fine … in theory.

The problem with FAM is that it’s really hard to get a perfect read on when you’re ovulating to find these “safe days.” Everyone’s body, and period, is different, so there’s no one set of guidelines that are guaranteed to work. And none of the various methods people use to get insights into their cycle, whether that’s temperature, mucus, or something else, are perfect.

For example, the estimate that ovulation takes place around days 14–16 is based on the assumption that your cycle is 28 days long,6 which isn’t true for most people.12 If your cycles are consistently less than 27 days — just one day shorter than average — you can’t use the calendar method.6 And not everyone’s period is exactly the same from one month to another, either — things like stress, travel, alcohol, and more can throw things off.12 People also start ovulating at different times throughout their cycle. In fact, one study of 221 women showed that they had at least a 10 percent probability of being in their fertile window — AKA when they could get pregnant — anywhere from day six to day 21 of their cycles.13

Put together, it means that using the calendar method alone is a very bad idea. That’s why many people who use FAM will rely on things like temperature. But these measurements also have their drawbacks.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

Your body temperature goes up slightly when you ovulate, by around one half to one degree Fahrenheit.5 But things like moving around or drinking a cup of hot coffee can raise your body temp, throwing readings off. To do it right, you’ll need to take your temperature first thing every morning, before you even get out of bed. Keep in mind that your body temperature can change from day to day for other reasons as well, like stress or sleep patterns.14-15 And remember that body temperature only increases after you start ovulating, meaning it can’t indicate when you’re about to start.

Measuring cervical mucus is a slightly more trustworthy way of telling when you’re about to ovulate. In the days before ovulation starts, the mucus gets thinner, and looks and feels kind of like egg whites.5 It’s a more consistent ovulation marker, but measuring cervical mucus takes practice and consistency to get right. And it also requires … measuring your cervical mucus.

Some people that practice FAM will rely on test strips or electronic monitors that measure levels of , which increases before an egg is released, in urine.16 Used alongside other methods like temperature or cervical mucus, these tests can give you some assurance around when you’re ovulating. But they’re also not perfect: The pro-FAM author of a 2019 editorial in the New York Times relates being horrified by what turned out to be a false ovulation reading on her test.

Using FAM is tricky, and some people recommend practicing it for months or even a year before fully trusting it as . Meanwhile, the consequences of slipping up are real and life-altering.

Is adyn right for you? Take the quiz.

Can FAM ever be effective?

The lower efficacy and increased difficulty of using FAM notwithstanding, some people say they prefer it over other methods of . Some people have religious objections to other methods of , while others simply don’t want to take hormones or put something like a copper IUD in their body.

In some cases, people appreciate the greater awareness of their body and their cycle they get from practicing FAM. Paying attention to your cycle and your body definitely isn’t a bad idea, and it can help you feel more in tune with what’s going on inside. Remember, you can always use FAM alongside another kind of if you just want to listen to your body a bit more.

If you do choose FAM as , you should pair multiple methods for the most accurate information. You can also use an app like Natural Cycles, which pairs body temperature data with an algorithm the company says helps time ovulation. In a study by the company’s founders, the method was 93 percent effective with typical use.17

But for people with irregular menstrual cycles, apps like Natural Cycles that are based on timing are also far less effective. That means you might be given lots of “red days” where you can’t have unprotected sex because the algorithm isn’t sure whether you’re ovulating or not. And, as the company’s website notes, things like stress, illness, hormonal use, and more severe diets can throw off the algorithm’s effectiveness as well.18

That said, if you’re ready to take your temperature every day, and willing to trade some effectiveness, you can try FAM. But it is worth keeping in mind that even if an app like Natural Cycles is 93 percent effective, that’s significantly worse than the 99 percent effectiveness of an IUD. And outside studies of FAM indicate that it can be substantially less effective than 93 percent: A review study from 2018 looking at multiple kinds of FAM found that the effectiveness varied substantially, from around 98 percent to less than 70 percent.19 More worryingly, the study authors note that most studies of FAM aren’t high quality, meaning it’s tough to trust their conclusions.

It’s also important to remember that the rigorous self-monitoring that accompanies FAM is harder for some people than others. It takes a certain level of privilege to be able to consistently take your temperature every morning, monitor your cervical mucus, or take a fertility test every day — not everyone has the time or resources to do this.

Even if it really is 93 percent effective, FAM could still result in an unplanned pregnancy. Depending on where you live in the United States right now, those odds could entail a substantially higher risk should you choose to seek out an abortion. That could even mean fines and prison time in some states, just for traveling to another state for a procedure that’s legal there.

What kind of is right for me?

The kind of that’s right for you is the one that meets your needs — and those are different for everyone. At adyn we only recommend that’s highly effective — which means 98 percent effective or better with perfect use. Highly effective options include the IUD, ring, patch, and pill.20

Right now, there’s not enough evidence to say that FAM meets that bar. While one paper from Natural Cycles does say that it’s 98 percent effective with perfect use, other research not affiliated with the company says the effectiveness of FAM could be substantially lower. And that’s for perfect use. FAM is hard to do right, meaning that perfect is a tough thing to achieve.

People with irregular cycles (read: lots of people), also can’t use FAM confidently, meaning it’s not a great option for a significant number of people looking for they can trust.

Even if you’ve had a bad experience with one kind of , it doesn’t mean that there’s not a more ideal option for you. The right can help with things like acne, period cramps, and more, in addition to providing you with .

Want to learn more about finding the right ? Read more about The Birth Control Test.

-

- Mayo Clinic Staff. “Rhythm method for natural family planning.” MayoClinic.org (2023 Mar 07: Accessed 2024 Jan 29).

- “Natural family planning (fertility awareness)” NHS.uk (2021 Apr 13: Accessed 2024 Jan 29).

- “How effective is contraception at preventing pregnancy?” NHS.uk (2020 Apr 17: Accessed 2024 Jan 29).

- “Rhythm Method.” ClevelandClinic.org (2022 Aug 12: Accessed 2024 Jan 29).

- Pallone, Stephen R., and George R. Bergus. “Fertility awareness-based methods: another option for family planning.” The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 22.2 (2009): 147-157.

- “What’s the calendar method of FAMs?” PlannedParenthood.org (Accessed 2024 Jan 29).

- “Basal Body Temperature” ClevelandClinic.org (2022 Dec 19: Accessed 2024 Jan 29).

- Peck, Rebecca. “Case reports of the Marquette method.” The Linacre Quarterly 80.1 (2013): 24-30.

- “Institute for Natural Family Planning Model” Marquette.edu (Accessed 2024 Jan 29).

- Marnach, Mary. “What ovulation signs can I look out for if I’m trying to conceive?” MayoClinic.org (2022 Dec 07: Accessed 2024 Jan 29).

- Jacobson, John D. “Pregnancy – identifying fertile days” MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2022 Jan 10: Accessed 2024 Jan 29).

- Münster, Kirstine, Lone Schmidt, and Peter Helm. “Length and variation in the menstrual cycle—a cross‐sectional study from a Danish county.” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 99.5 (1992): 422-429.

- Wilcox, Allen J., David Dunson, and Donna Day Baird. “The timing of the “fertile window” in the menstrual cycle: day specific estimates from a prospective study.” BMJ 321.7271 (2000): 1259-1262.

- Vinkers, Christiaan H., et al. “The effect of stress on core and peripheral body temperature in humans.” Stress 16.5 (2013): 520-530.

- Lack, Leon, and Kurt Lushington. “The rhythms of human sleep propensity and core body temperature.” Journal of Sleep Research 5.1 (1996): 1-11.

- “Luteinizing Hormone (LH) Levels Test” MedlinePlus [Internet]. (Accessed 2024 Jan 29).

- Berglund Scherwitzl, Elina, et al. “Fertility awareness-based mobile application for contraception.” The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care 21.3 (2016): 234-241.

- “Can I use Natural Cycles if I have irregular cycles?” NaturalCycles.com (2024 Jan 29).

- Urrutia, Rachel Peragallo, et al. “Effectiveness of fertility awareness–based methods for pregnancy prevention: A systematic review.“ Obstetrics & Gynecology 132.3 (2018): 591-604.

- “Appendix D: Contraceptive Effectiveness” CDC.gov (2014 Apr 25, Accessed: 2024 Jan 29)