For most people who take birth control pills, they receive a month’s worth of pills in each packet. The first three weeks of pills contain hormones that stop your from releasing an egg. But the last week of pills don’t. Called pills, they are made of an inactive substance like starch or sugar, and function as a placeholder, mimicking the menstrual cycle that would happen if you weren’t taking . But although having a week in pills is commonplace, there is no medical reason for pills. So why do we use them? You can blame the Pope, at least in part.

The world was a very different place back when pills were being developed in the 1950s. Although popular attitudes about sex and were shifting, it was happening slowly. Many states banned contraceptives, with religious attitudes about sex before marriage having a major influence on policy. One of the people who developed the first birth control pill, John Rock, thought that if he could make the Catholic Church see as “natural,” that would influence church officials to accept for Catholics around the world.

He had good reason to think that. Back in 1930, Pope Pius XI had issued a proclamation (named Casti Connubii, Latin for “Of Chaste Wedlock) that prohibited artificial methods of . Then in 1951, Pope Pius XII announced that the rhythm method for was not a violation of church doctrine, because it was a “natural” method. Rock tried to make the case that the pill was “natural” because it used hormones that already occurred in the body, and maintaining a regular menstrual cycle was a key part of his argument. A devout Catholic, Rock went as far as to publish a text pleading the Catholic case for pills in 1963, “The Time Has Come: A Catholic Doctor’s Proposals to End the Battle over .”

The religious influence to make the design of the pill as “natural” as possible wasn’t the only push in that direction: popular understandings about the need for regular menstruation influenced the creation of a week in birth control pills, as did the reaction of some women who received the earliest U.S. trials.

Rock and Gregory Pincus, another member of the team developing the pill, observed that patients taking the hormones became convinced that they were pregnant because they had not had a period, and then distressed when they learned that they weren’t pregnant after all.

Pincus was the one who initially had the idea to have the patients stop taking the hormones for five days per month. The company that supplied the hormones to Pincus had also informed him they did not want to be involved with a product that would change the natural menstrual cycle. And so even from the first clinical trials of the pill, a week for menstruation was always built into the pill’s design.

Menstruation was also central to the pill getting approval by the Food and Drug Administration, since it wasn’t initially approved as a method, but rather as a treatment for menstrual disorders. This was a strategic move – contraceptives were controversial and still illegal in some states – and it paid off. The FDA approved the pill in 1957 for menstrual disorders and , because trials had shown that women who took the pill for a period and then stopped taking it were more likely to become pregnant. Each pill bottle had a warning on it stating that the pills prevent ovulation (and implicitly advertising that it could work as a form of ).

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

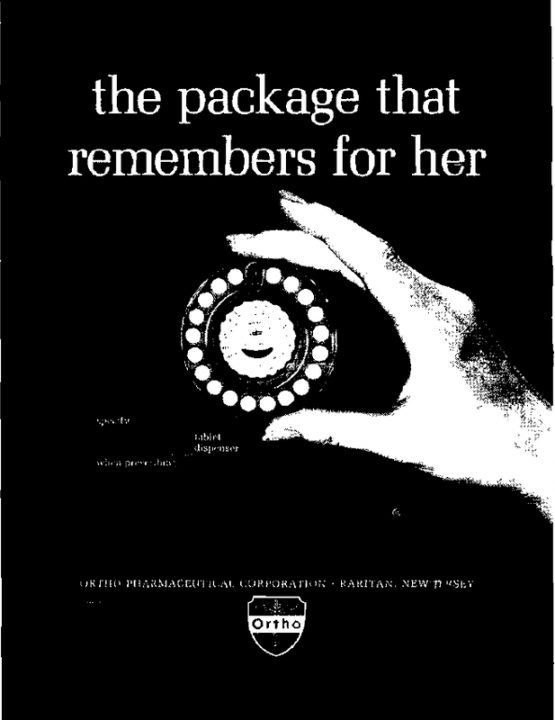

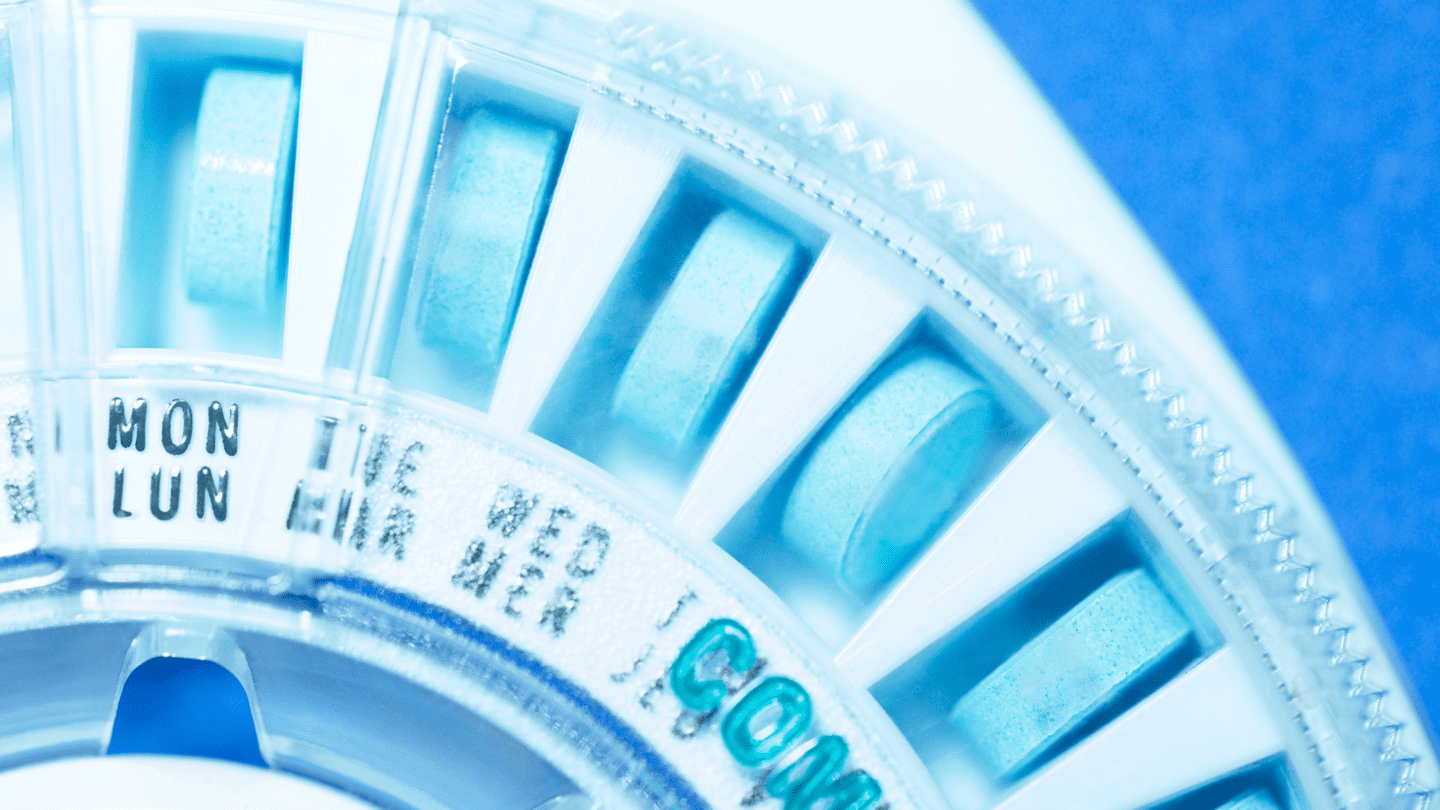

When it came time to manufacture and market the pill, sexist ideas about women being forgetful influenced product design. David Wagner, who designed one of the first pill dispensers for birth control pills, was worried that his wife wouldn’t remember to take the pill regularly. He designed a dial-style pill dispenser that indicated the day for each pill. This product design incorporated the week and more firmly entrenched it into common usage. “The package that remembers for her,” one ad read.

Image source

Although Rock was ultimately unsuccessful in convincing Catholic leaders to embrace the pill in church doctrine, that didn’t stop it from becoming widely adopted by Catholics. A 2016 Pew Research Study found that 89% of Catholics have no moral issue with the use of contraceptives, despite the Catholic Church’s steadfast official opposition. But only recently have pharmaceutical companies started to adopt more options for consumers who want the birth control pill without the religious baggage– that is, the week.

89% of Catholics have no moral issue with the use of contraceptives, despite the Catholic Church’s steadfast official opposition.

Continuous cycle birth control pills (where you have no period) and extended cycle pills (which make periods more infrequent) are increasingly on the market as an alternative to birth control pills with the typical week. Health experts have found that there is no medical reason to have a period, and in fact, the bleeding that happens during a week isn’t an actual period – it’s known as withdrawal bleeding, and is different in the quantity of blood, composition of it and timing.

Is adyn right for you? Take the quiz.

Perhaps the week may soon become a thing of the past as more people use continuous and extended cycle methods of . Maybe, but the practice has held on for more than sixty years without a solid medical reason – so the murky influence of the Catholic Church on might just continue on into the future.