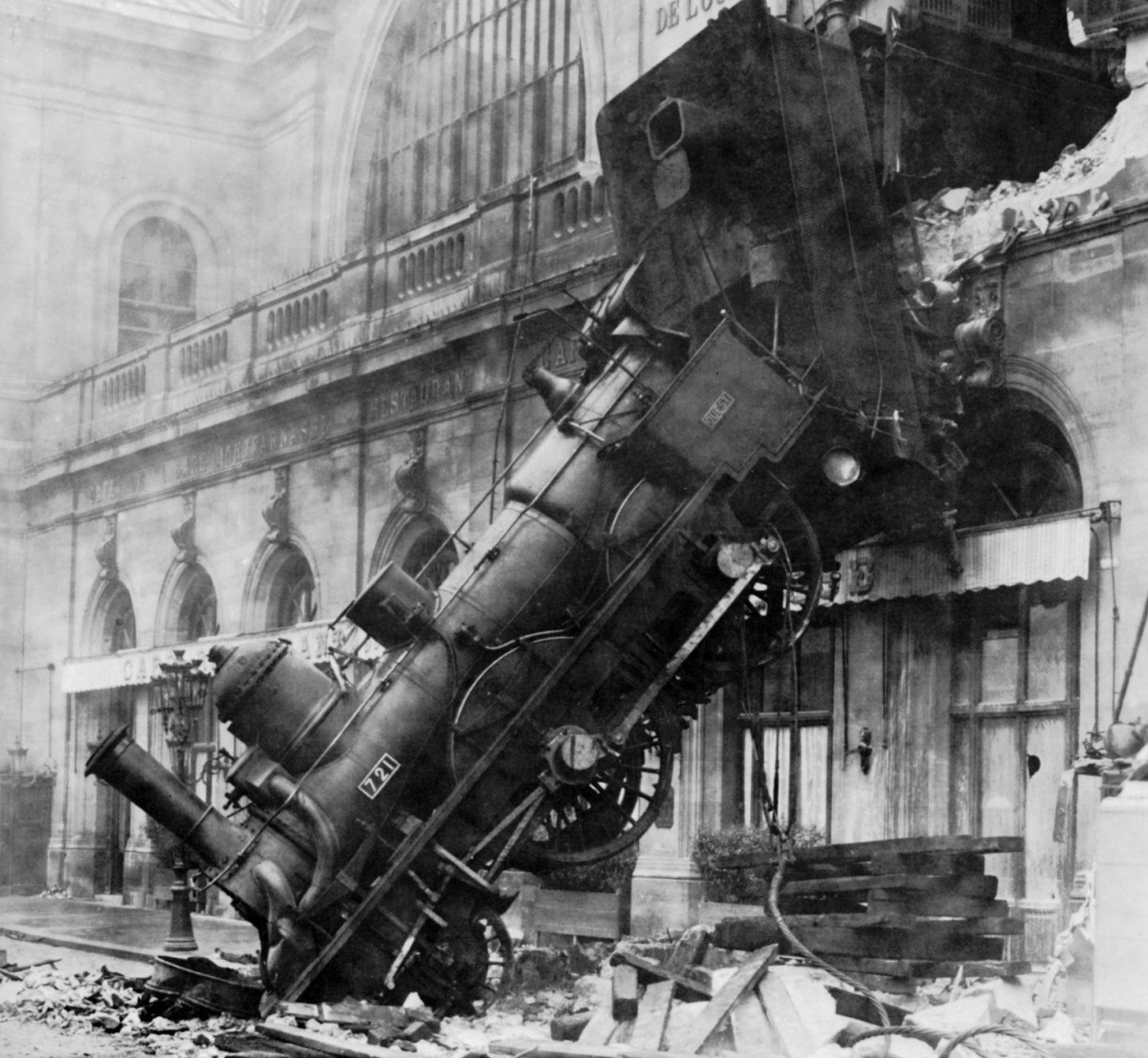

Entrepreneurs at tech startups are likely to hear the Mark Zuckerberg adage that it’s important to “move fast and break things.” The concept that moving quickly to get ahead of competitors and get products in customer hands is appealing, but it doesn’t work across all industries.

Health care is one of the fields where moving too fast and “breaking” things could have disastrous results. Theranos is just one example where this type of philosophy was a horrendous idea. Lacking the R&D necessary to actually prove its product worked, the company delivered health test results to patients that were wholly inaccurate, for which it was rightfully sued. It takes just one misdiagnosis to destroy trust in a company’s product, especially when that result is as life changing as a positive (but false) result for an HIV antibody.

Here are eight reasons why moving fast and breaking things in health care just doesn’t work:

These products affect people’s lives.

Health care and health care products affect users’ health and the quality of their lives. If a consumer product or specialty good malfunctions, it might cause an inconvenience and possibly the loss of money (if not covered by a warranty). But if a pacemaker fails or a diagnostic test produces a false negative, people can die. When the stakes are this high, companies must hold themselves to an impeccable standard.

This is a highly regulated space.

This is a highly regulated space — and for good reason. An alphabet soup of laws, regulations, and regulatory bodies (think FDA, CLIA, , IRBs, GINA, for starters) exist to protect everyone: whether you’re applying a Band-Aid, buying over-the-counter medicine, or having surgery. Compliance requires planning, resources, and diligence, all of which take time. Rushing protocols puts all health care consumers at unnecessary risk.

Is adyn right for you? Take the quiz.

Products must perform in multiple dimensions.

A successful health care product considers the needs of consumers, clinicians, regulatory bodies, and health care payers. A great product has utility for all of these stakeholders. Continuous glucose monitors (CGM) for people with diabetes are a good example: they have demonstrated clinical utility, their use makes life easier for the user, and they provide rich data for the user and their clinicians. For a CGM to work, the system itself must be rigorously tested for accuracy and reliability, it must be applied properly to the body, and the user has to have comfort and familiarity with the accompanying technology, like a smartphone app or a dedicated receiver. If any one of these components fails, the product no longer serves its purpose.

Education must be baked in.

The majority of consumer goods are things people recognize and know they need or want, like shoes or cars or popcorn. But when a company is creating a new category or marketing a new invention — especially one rooted in science — it has to educate potential users before it can assess whether they need or want its offering. Building high quality, accurate content is time consuming, especially when it is technical content. Key messages and value propositions vary for different audience segments — providers, regulatory bodies, insurance companies, employees, as well as consumers with varying levels of prior knowledge.

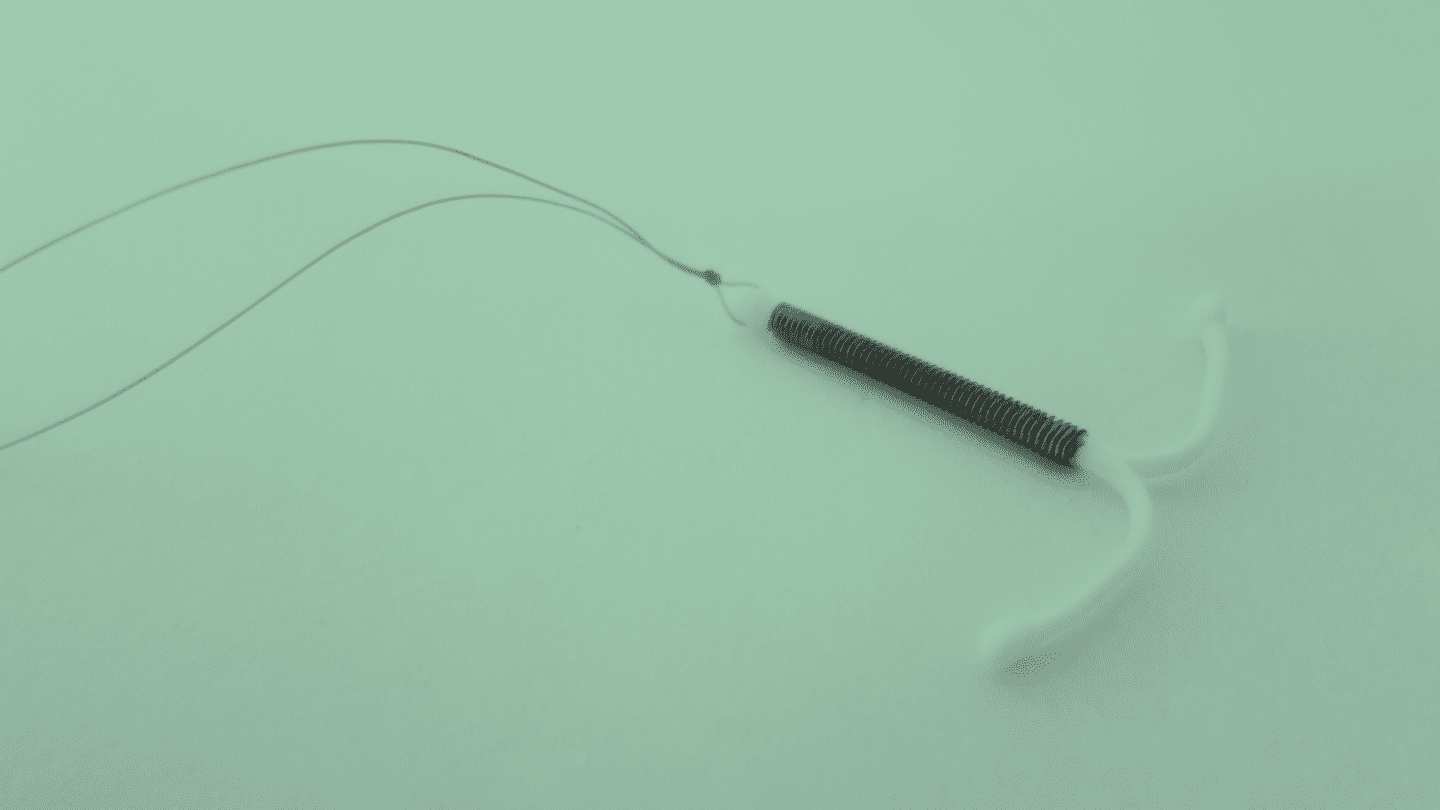

Especially in consumer health tech, education takes time — not to mention that the prospective customer is often not the only person involved in the decision to purchase. Purveyors of any good health tech product recognize that investing in educational content is essential to securing buy-in from all stakeholders. At my company, adyn, we know that people considering often engage in conversations with parents, siblings, friends, providers and even complete strangers on social media about how to choose the right . For us, this means creating resources that help a person have those conversations, and come away feeling empowered and educated. And for scientific research, publishing in peer-reviewed journals is another channel for educating and building credibility that takes time and effort.

Like what you’re reading? Get the latest straight to your inbox 💌

Navigating a labyrinth isn’t easy.

The health care system is complex and entrenched. Patients experience this firsthand when they navigate changing doctors or insurance plans but the full picture is even more challenging. From socioeconomic barriers preventing access to care to regulatory differences between states, even the best idea can’t always be executed without jumping through several flaming hoops. Many companies deeply believe they have a mission that will revolutionize the U.S.’s broken health care system. But a system this bureaucratic and complex is difficult to navigate, integrate into, or evolve within.

Looking for a quick and easy approach within a labyrinth this complex probably won’t end well. The collapse of uBiome is a lesson for health care companies trying to outsmart the health care system: routinely billing a patient’s insurance company for repeat tests on old samples isn’t going to fly. Loss of trust generally leads to loss of vision.

Creating a culture of curiosity to drive innovation means building with time to fail.

Innovation and scientific discovery come from deeply evaluating something without the presence of a ticking time bomb. Creating a culture where it’s okay to fail means teams aren’t scared to try something that might actually be game changing. It also disincentivizes falsification of data. Striving for excellence in serving customers is critical, and time can sometimes be the difference between “good enough” and a breakthrough.

Building trust doesn’t happen overnight.

When it comes to sharing personal health data, reasons not to trust brands are abundant — from a lack of secure systems (the 2015 Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield data breach is an example) to undisclosed sharing practices (like health tracking apps that automatically transfer data to Facebook or Google). In addition, social media is flooded with medical .

Gen Z individuals have a lot of influence in determining what health care technologies are adopted en masse, but they are discerning consumers, unafraid to cross-reference multiple sources of information before committing. Building trust isn’t a single action item; it is a continual process of listening, communicating, refining, and responding.

Building trust isn’t a single action item; it is a continual process of listening, communicating, refining, and responding.

A revolutionary vision lacking a scientific basis will fail to change the standard of care.

Accumulating the knowledge needed to create game-changing health care products takes years of practice. Surface-level or incomplete knowledge often results in products that are flawed from conception because the fundamental scientific foundation is missing. To understand the complexities of human biology through even a single lens (genetics, physiology, oncology, and the like) requires rigorous training and cannot be learned in just a few months while building a beta product. With enough capital, almost anyone can build an app or a device. But to truly innovate, a deep understanding of the science and the ability to produce measurably improved health care outcomes are what’s needed.

When it comes to health care, the idea of “moving fast” needs to be qualified. Yes, health care tech is a competitive space and yes, the pandemic has taught us that timely access to health care data and innovative products is important. But these innovations must be backed by scientific results, which means they cannot be rushed. Guardrails that are designed to protect patients, validate the science, and provide medically-actionable results are too important to ignore for the sake of moving fast.

This piece was originally published by STAT.